“My father never dies” - Nizar Qabbani

Dear Adam,

The black plastic bag didn’t look like it contained anything of importance. Tucked away at the back of your late grandpa’s closet, it appeared as though it was tossed there and forgotten. I had finally worked up the courage to go through his things to decide what to keep and what to donate. I reached into the bag and pulled out its contents: old papers, letters and a couple of telegrams. There didn’t seem to be anything special about them and then I noticed one letter that was noticeably more formal than the others.

It started: My beloved Muawia. I flipped the letter over to see who was the sender: It was Rashaad Ruweha, my grandfather.

(The first letter from your great grandfather that I discovered in my father’s belongings)

The letter was from 1959 when your grandfather started his studies in Cairo University, he was 17 at the time. He had won a scholarship to study aviation engineering, but a chance meeting convinced him to change his specialisation to civil engineering even though it meant forfeiting the scholarship.

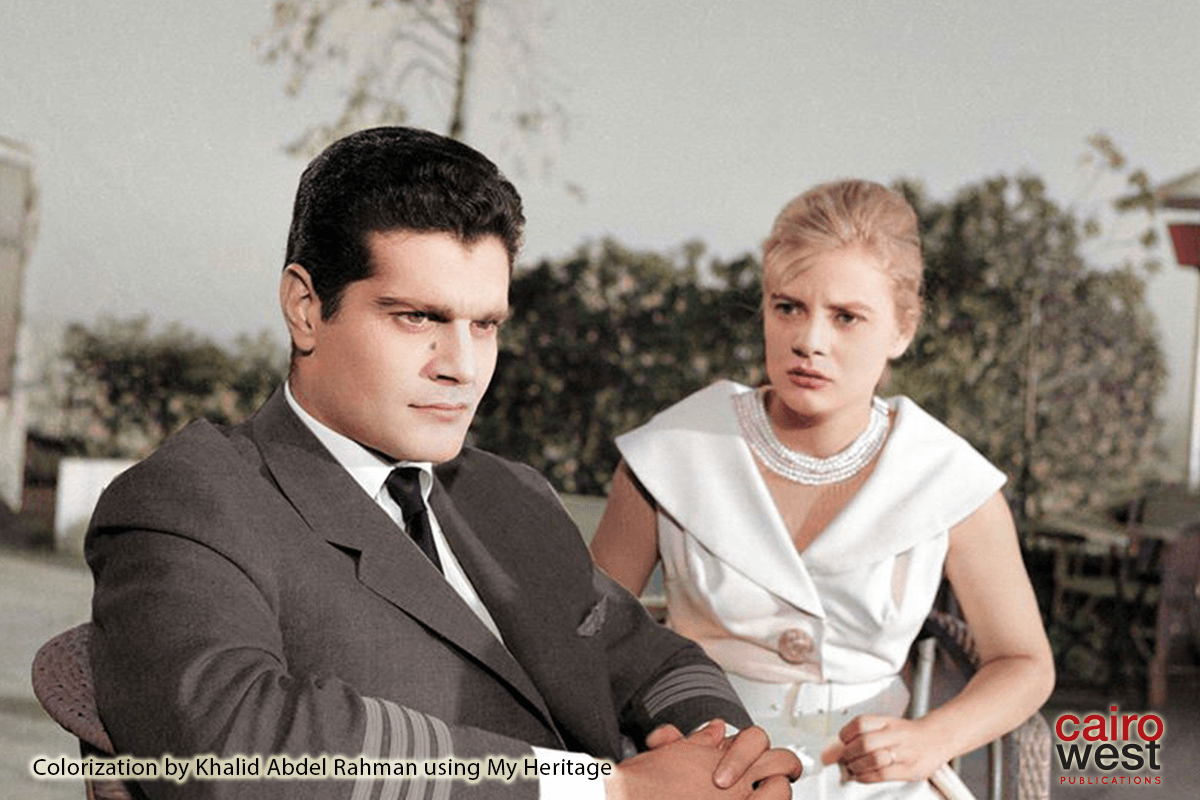

At that time, Syria and Egypt were a political union called the United Arab Republic led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, the instigator of the original MAGA (Make Arabs Great Again). Cairo at the time was the largest metropolis of the region with 3,5 million inhabitants, Damascus and Baghdad were older but Cairo had become a hub for arts, culture and business, and the political lynchpin of the region.

By comparison, our hometown of Latakia had 75000 inhabitants at the time. I did the maths for you: Cairo was 46 times bigger than Latakia!

(Colorised still of Omar Sharif and Nadia Lutfi from one of their movies. Check link for more images from Egypt’s golden era: https://cairowestmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Aflam-web12.png)

(Colorised still of Omar Sharif and Nadia Lutfi from one of their movies. Check link for more images from Egypt’s golden era: https://cairowestmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Aflam-web12.png)

This, on its own, would’ve been enough to give your great grandfather sleepless nights but not only was your grandpa quite young to start uni in such a behemoth of a city, he had also the disadvantage of having had a stifled adolescence.

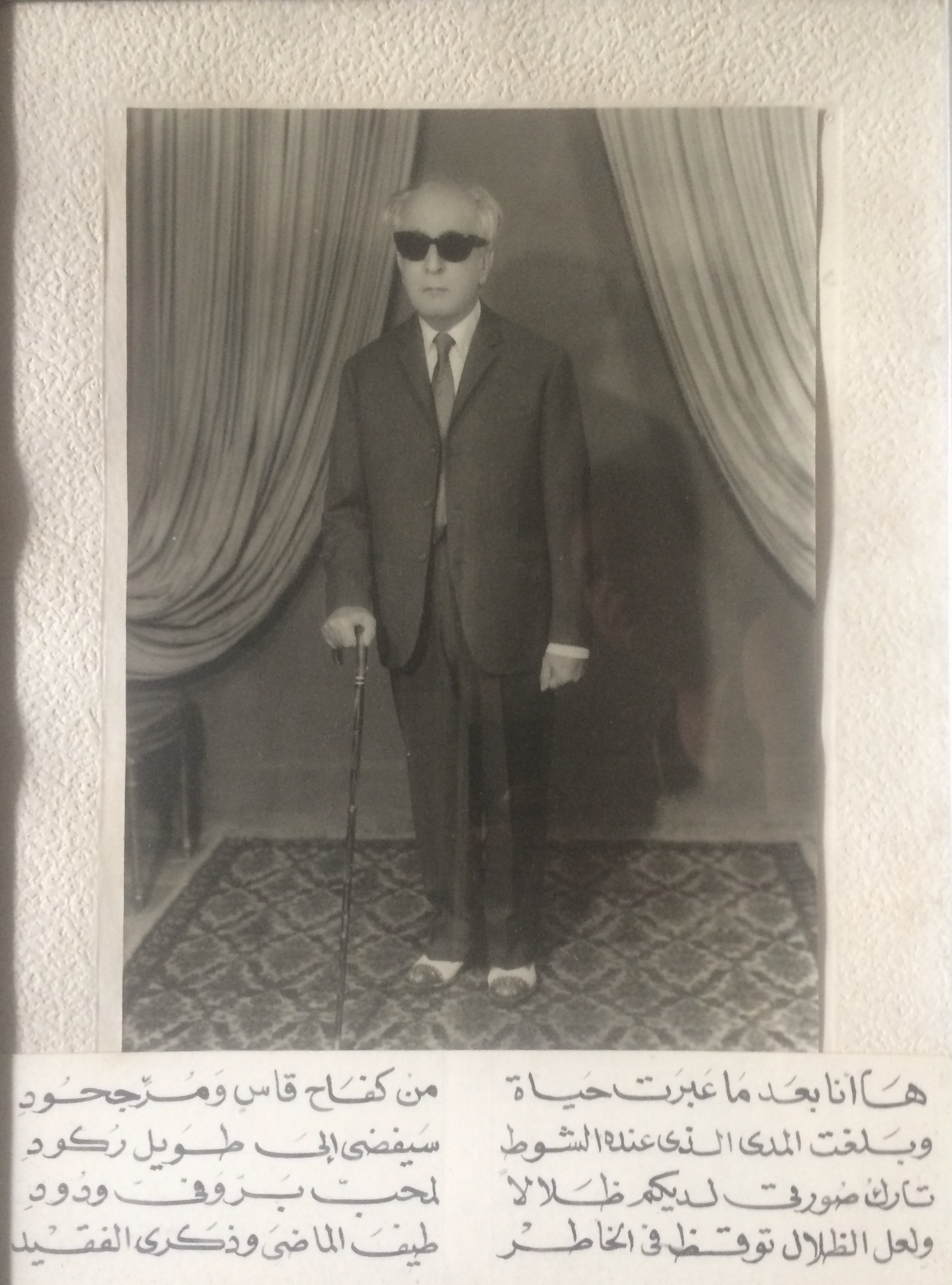

He was just 6 years old when he was tasked with escorting his blind father around town after school. My grandfather may have been blind since he was 3, but he had overcome that handicap to become an accomplished poet, a political activist who established his own newspaper called “Al Jalaa’” (Independence) and a pillar of his local community.

(Photo of Rashaad Ruweha with a short eulogy that he composed - Date unknown)

(Photo of Rashaad Ruweha with a short eulogy that he composed - Date unknown)

As the youngest boy of 8 children, your grandpa had to give up his free time to be with his blind father. Being absent-minded (a trait that he suffered from all his life), would often cause him to take a wrong turn and thus incur the wrath of his short-tempered father who’d slap him on the spot.

The emotional scars from public reprimands and lack of normal childhood stayed with your grandpa for the rest of his life. If you read his autobiography, you will sense the melancholy of those years and how your grandfather remained inconsolable about his stolen childhood. But moving to Cairo didn’t just give him a chance to shed the yoke of servitude, it would eventually allow him to reinvent himself in the image of the matinee idols of that era: a dashing and cocky debonair who sees the world as his oyster.

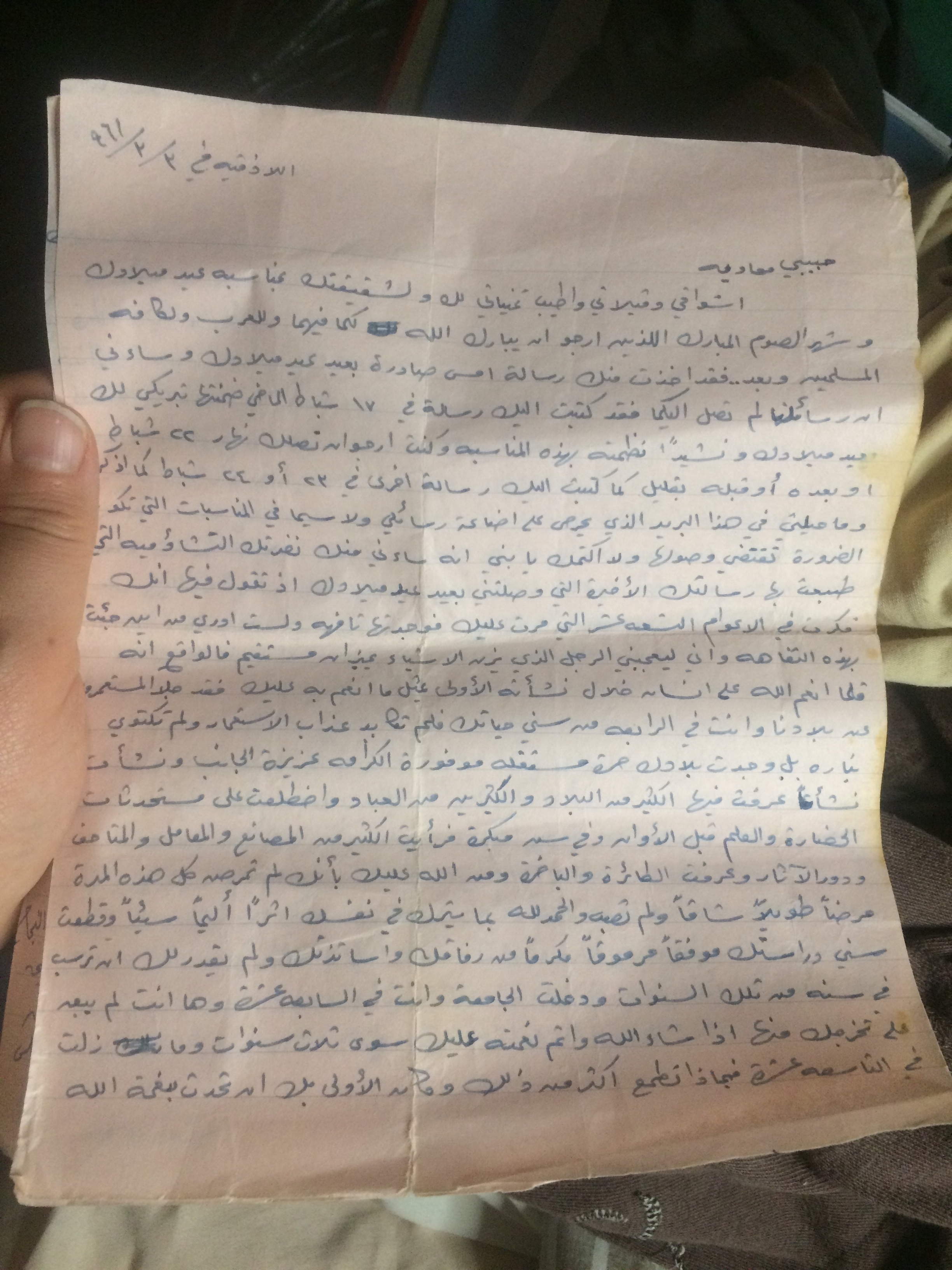

But that transformation was not instant nor painless. Overwhelmed by the workload of engineering studies as well as being truly independent for the first time in his life, Dad wrote to his family often either to ask for advice or just to let off steam whenever things got too much for him.

In one letter, your great grandfather describes the excitement whenever they found a letter in the post box from Egypt. The letter would be read aloud so everyone could hear what your grandad was up to. Since your great grandpa was blind, he had to dictate his reply to whomever was on hand, and his responses always contained some advice or reprimand as he would see fit. There are times when the letters were tender and humorous. I laughed out loud at one letter where he was telling his son how happy the family was to hear he passed his exams and then the old man says: “but I’m only congratulating you by extension as it is I who should get all the credit!”

You see, even though your grandad was not his father’s only child (he had 3 brothers and 4 sisters), Rashaad Ruweha considered his youngest son to be the only one with a shot at greatness, something that the old man craved as he felt that his blindness had denied him any chance of a proper education and a meaningful career.

The letters were not merely a way of staying in touch, they were a road map that summed up what my grandfather felt was necessary for success in life.

For him, faith was essential and nonnegotiable and the letters are full of quotations from the Quran that he used to support his views. You have to remember that your great grandfather knew the entire Quran by heart. His parents wanted him to have a way of earning a living to supplement what he’d inherit from them. As a blind man, he had extremely limited options, but by learning the Quran he could become a Moqre’ who gets paid to recite verses from the holy book at funerals, wakes and religious occasions. In those days before LPs and CDs, Moqre’s were hired like we hire a DJ for a party today!

Yet, somehow, the blind boy was able to defy all expectations and, despite lacking a formal education, he was able to teach himself Turkish and French and use his mastery of the Arabic language to make a name for himself. Which brings us to the second thing that your great grandfather was passionate about: politics, namely Arab nationalism.

There isn’t a single letter from your great grandfather to his son that doesn’t include a reminder to honour the homeland, but he wasn’t referring to Syria. In his mind, the homeland would ideally unite Arabs “from the (Atlantic) Ocean to the (Arabian) Gulf”- the United Arab Republic, however, was a good start. When Syria seceded from the union in 1961, he felt betrayed and chose voluntary exile to Egypt rather than stay in a country that would not honour his dream of a untied Arab nation.

I can only imagine his dismay at how far the successive apples (your grandpa, me and you) have fallen farther and farther from the tree especially in terms of political beliefs. He was insulted when, at their last meeting, your grandpa said the French had done good things for Syria. The French had sent my grandfather to a local version of the Gulag for his nationalist activism so I can understand his anger but, like your grandfather, I feel more affinity for Europe than for the Great Arab Homeland. Sorry Grandpa!

But there’s one more common denominator to all the letters and it’s the only one that your grandfather took to heart and made sure he passed it on to both you and me: grit.

I never met my grandfather. What people told me about him seemed to to revolve around three things: his blindness, his short stature and his even shorter temper! But reading his letters showed me another side of him. He was extremely principled which made him often come across as condescending and sanctimonious, and yet, there was a dignified stoicism to his words.

He was dealt a bad hand but instead of using that as an excuse, he lived his life on his own terms and he wanted his son to do the same. When I read what my grandfather wrote to my dad, I always hear it in my head in Dad’s voice because it’s what he used to say to me verbatim.

I used to find my dad’s calls to “toughen up”, “keep a stiff upper lip” and “take it on the chin like a man” infuriating. I’d often yell back at him: “I’m not even a man so why do you keep saying that to me?”

(Let’s not forget that I do have a brother so I never understood why the lectures on being a man were reserved exclusively for me)

But it wasn’t just the lectures that drove me crazy. Your grandpa would often resort to merciless taunts to make his point. He’d call me a scaredy chicken any time he felt I was being weak (I know the proper expression is a scaredy cat but it’s a chicken in the Syrian version).

And then there was his infamous barb: “Tomorrow is Nagging Day”.

I’ll tell you the story behind it just to lay that ghost to rest:

A woman who was a relentless nagger nearly drove her husband crazy. He considered leaving her but he was finally able to reach an agreement with her to save their marriage. She could nag on one day and give him a break on the following one and so on.

The on/off arrangement worked for a while but the woman was unhappy at having to stay quiet half of the time so she found a way to have her cake and eat it. On the day she was supposed NOT to nag, she would chase her husband around chanting:“Tomorrow is Nagging Day!”

Your grandpa loved to tell this story and claimed that I often sounded like the nagging wife. His definition of nagging was very broad: from complaining to whining, and sulking, even asking for something repeatedly would get him wagging his finger in my face and saying: “Tomorrow is Nagging Day”

The tactic worked but it was beyond irritating!

So you can imagine my surprise when I found out in one of your great grandfather’s letters about how my father responded to congratulations on his 19th birthday by COMPLAINING about his “trivial” life thus far!

The old man was quick to set the record straight for his whiny son. I thought I’d translate that part of the response for you to put that period into context:

“… Rarely has God blessed a human in his early years as he blessed you as the [French] occupation left our country when you were 4 years old so you never suffered from the pain of occupation and weren’t burned by its fire. Instead, you’ve found your homeland free, independent, with full dignity and honour and you grew up in a way that allowed you to know many countries and people.

You were exposed to the latest in civilisation and science early in your life, you saw many factories and museums and you got to know the plane and the ship. You were blessed that you were never severely sick and you were never hit by anything, thank God, that would leave a painful mark in your spirit.

You were successful and distinguished in your studies, honoured by your classmates and teachers. You never failed a year of study and you entered university at the age of 17 and here you are, God willing, just 3 years away from graduation.

What could you want more than that? You should be grateful for the gifts God has endowed you with, appreciate them, feel happy and know the value of what God has blessed you with”

I won’t lie! This sermon brought a smile to my face.

I’m sorry, I know it’s inappropriate to laugh at one dead man scolding another dead guy but this felt like my grandpa was taking my side, albeit posthumously, like grandparents often do.

But that moment of glee evaporated a few lines later when the old man gave your grandpa a warning that was, in hind sight, prophetic.

He was trying to get his son to change his pessimistic outlook and tells him “you never know if the future will be worse than what has passed”.

Remember this letter is from 1961. The 54 years that followed were a brutal gauntlet that your grandfather had to run enduring one painful strike after another.

He became a millionaire at age 40 only to lose everything not once, not twice, but 3 times.

His two marriages failed and almost every business partner he had cheated him of his hard earned money.

He was sentenced to prison in absentia over SIX US Dollars. Syria has very strict laws around hard currency and doing export and import was a mine field. Your grandpa stepped on such a mine when he returned the exact amount he took in hard currency but he didn’t account for the the bank fee. The missing 6 USD was wired as soon as he noticed the deficit but he was found guilty nonetheless. That sentence kept him stranded in Poland for the remainder of his life and he wasn’t able to return to Syria again.

He would lose sight in one eye, nearly get deported from Poland, and almost ended up homeless and destitute on the streets of Warsaw.

On the lighter side of mishaps, a bridge literally dropped on a lorry that was carrying a shipment of prime timber that he had imported. And then there was that time when he sold a truck of mozzarella cheese but his partner forgot to insure it. The client was in Kuwait and the truck arrived just as Saddam Hussein’s forces had stormed the country. Because the shipment was not insured, they were not eligible for any compensation.

The list of misfortunes goes on and on and on.

I find myself holding back tears as I recount how much he went through and yet he would retell these stories with only a hint of bemusement at his bipolar luck. He was a man who -in the words of Rudyard Kipling- met both triumph and disaster and he took both in stride. Was it his father’s old warning that made him grow such a thick skin? Maybe, but I’m not so sure.

It’s more likely he had inherited his father’s ferocity who, as a young (blind) lad, would spur his horse to go to the top of the local quarry or ride so deep into the sea that he couldn’t tell in which direction the shore was.

These two were one of a kind in the family. They didn’t endure because it was the dignified or manly thing to do. In fact, after years of challenges, they seemed to abandon the resigned acceptance of the biblical Job. They did remain stoic to the end but it was tinged by a manic defiance as though they were saying to the Universe:

“I can do this all day!”

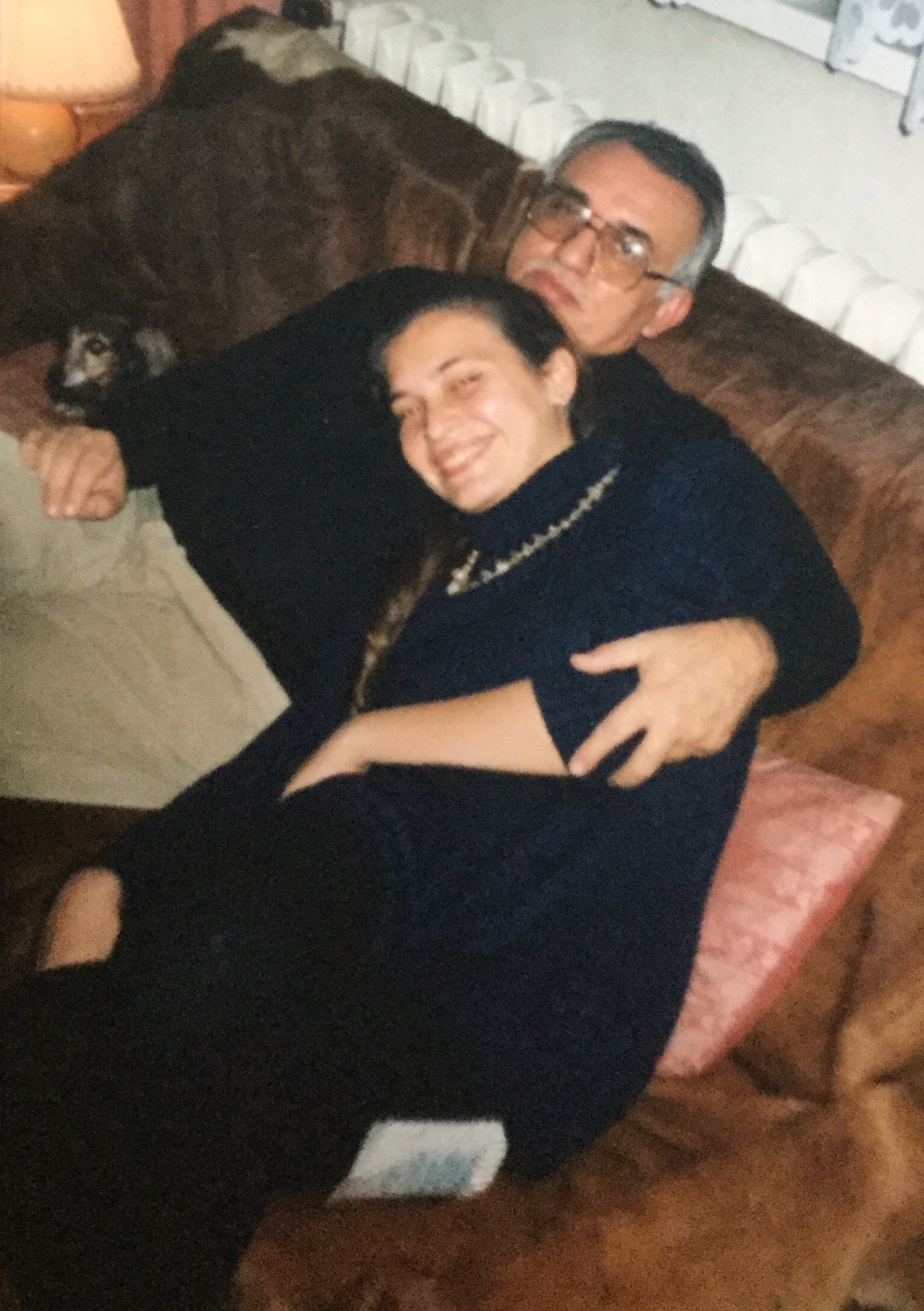

(Me and Dad in Warsaw, sometime in 2000)

(Me and Dad in Warsaw, sometime in 2000)

I wish I could tell you that their story had a happy ending. It didn’t.

7 months after writing that letter to your grandfather, Syria seceded from the United Arabic Republic. I mentioned earlier that your great grandfather chose voluntary exile to Egypt as a form of protest. But the truth of the matter was that he had no choice. His political views were well known to the authorities and it was just a matter of time before he would’ve been arrested. However, his youngest daughter forced his hand when she recklessly climbed up the flag post in her school and ripped the Syrian flag and tossed it to the ground. As a result, she was banned from all schools in the country.

My grandfather, grandmother and their two daughters joined your grandpa in Cairo and the move would spell the downfall of the family.

With both of them forced to live in an alien city away from their family and friends, the bickering between my grandparents escalated to fights. Dad did his best to act as peacemaker but failed. He was about to start the last year of his studies and was under a lot of pressure from all sides but the situation had reached boiling point and my grandfather left the family home.

It’s not that he simply packed up his stuff and left; he walked out on the family and refused to take responsibility for his estranged wife and children. Dad had to find the money to provide for his mother and sisters in a foreign country as well as coming up with the fees to pay for his final year.

He had no choice but borrow the money he needed on the condition that he would pay it back once he graduated and got himself a job.

The fact that he graduated from university at the tender age of 22 with a mountain of debts is something that my dad could not forgive.

He was rightfully angry and refused to speak to his father.

In the meantime, and in order to protect his assets during the divorce proceedings, my grandpa bequeathed his assets to his oldest grandson, effectively disinheriting all his children- including those from his first marriage.

As a result, your great grandfather would find himself alone and penniless in exile and his only source of income was his stipend as a political refugee from the Egyptian government.

There are a few letters that show that my dad and my granddad resumed talking afterwards, with your great grandfather even sending his regards to my mum and asking Dad to give the kids (me and my brother) a hug.

But soon after that the tone soured again. I don’t know what brought about the accusations against Dad of betrayal and cruelty. Did the old man send similar letters to all his children to protest being abandoned in his last days to battle illness and poverty alone? Or did he again single out my dad because he considered him the most capable and thus the most culpable?

I don’t think we’ll ever know the answer to these questions. All I have is these heart-wrenching letters from a tattered black bag.

But what distressed me the most about reading these letters is how similar they were to a lot of the correspondence between my dad and me and it’s only by putting the two sets of letters side by side that I could finally understand why my dad was constantly bitter and combative.

He had found himself in the same situation that his father ended up in. He was living alone in a foreign country where he didn’t speak the language. He had lost one eye and was always afraid of losing the second. His business partners kept stabbing him in the back and to add insult to injury, my mum had left Syria and returned to her native Libya taking my brother with her. I joined them a year later because I was no longer interested in continuing my studies in the UK but my dad assumed I had taken my mum’s side and was constantly lashing at me at the slightest slip.

Now I know that he had simply internalised his father’s insecurities, paranoia, even his way of communicating with his children. Worse of all, he ended up repeating -almost- all of his father’s mistakes especially in his relationship with me.

I won’t go into the details here. This letter has already gone on for too long and it’s turning into a hydra that keep growing heads with every attempt to wind it down but there is one thing that I need to clear up with you and there is no better time or place to discuss it.

What truly scared me the most after reading these letters is the thought of this pattern repeating itself with me and you. Think about it a little bit: the scene is already set with almost identical parameters.

Here I am, alone in a foreign country. I have no home to return to. Financially, I’m in a better situation than my grandfather was in Egypt but much worse off than my dad. You are my only child and you’re on the cusp of leaving the nest and maybe even leaving the country.

How do I know I won’t turn into my father and his father before him wailing like a banshee about how you have failed me and deserted me in my old age?

That thought pained me and for weeks I dragged me feet on writing this letter to you because I was scared of how we will resolve this curse.

But you came to my rescue.

I was in the kitchen busy making lunch when you planted yourself on the high chair on the other side of the counter. You were in a good mood and you started telling me how you’ve realised that, despite every thing we went through and against all cultural expectations, you’re happy and at peace. And then you quoted Camus:

“The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.”

I was floored! You have no idea how proud I was of you for being happy and free and so wise. And it made me realise your happiness was the key to breaking out of our inherited vicious circle. We as a family, we’re addicted to drama, to anguish and to disappointment. You somehow managed to bypass all that muck and found a way to rise above our turmoil.

It was Camus who said:

“In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.

And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger – something better, pushing right back.”

You, my son, are our invincible summer. No more winters.

With all my love,

Mum

An Epologue (of sorts!)

As I was wrapping up this letter, I remembered that there was some form of closure for the tumultuous relationship between my dad and his father and you, in fact, were a witness to it. You were just too young to remember.

It was in 2007. You, your dad and I traveled to Egypt to meet up with your grandpa and celebrate Eid together. Dad asked me to find out where my grandfather was buried. He had been to Cairo several times since his father’s death but this time he was determined to visit his grave.

Here’s the blog post I had written about our adventure trying to find my grandfather’s grave in Cairo. We found the place where we were told Rashaad Ruweha was buried, though we couldn’t confirm it for 100% because the identity of the political refugees buried in the crypt is kept secret and can only be verified by writing to Abdeen Palace.

Still, we had enough information to believe that my grandfather was buried in that particular vault. Dad asked me to stand by his side and we read Al Fateha* together in your great grandfather’s memory.

As I think back to that moment, I now know it was my father’s way to show his father that he was still remembered and honoured by the presence of three generations.

I hope that one day we’ll go together to Cairo again and that we would read Al Fateha for your great Grandfather one more time. If I don’t make it, the cemetery is called Bab El-Wazir. Ask for the crypt of the political refugees. Tell Rashaad Ruweha that you’re Muawia’s grandson and that you’ve come to pay your respects. I know he’ll be happy you visited.

Love,

Mum (You and your grandpa on our 2007 trip to Cairo, Egypt)

(You and your grandpa on our 2007 trip to Cairo, Egypt)

* Al Fateha (literally “the opener”) is, in fact, the closing set of verses of the Quran. It is traditionally recited in memory of the dead but it’s also used to indicate a formal betrothal as it’s read by attendees when the bride’s father accepts the marriage proposal made by the groom’s family.