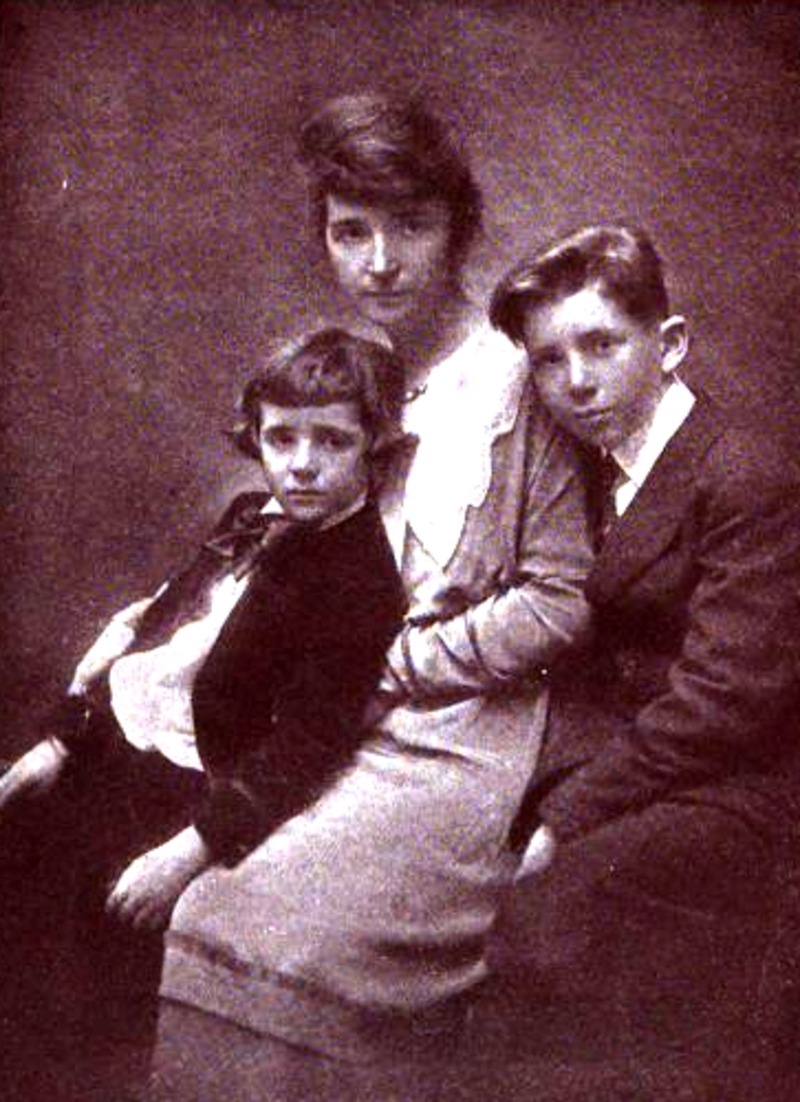

Margaret Sanger with her sons Grant and Stuart (c. 1919)

Margaret Sanger with her sons Grant and Stuart (c. 1919)

Parenthood remains unquestionably the most serious of all human relationships, the most far-reaching in its power for good or for evil, and withal the most delicately complex. I always tried to secure my sons’ confidence by being honest with them, treating them as though they had intelligence, and expecting them to use it. For the sake of companionship it was essential to be honest, no matter what the cost. Fortunately, the younger generation is not crumpled up when sharply confronted with the truth. They have cut through the regard to their feelings until they can say extraordinarily blunt things to each other and yet not be hurt. And with this they have invented a new language; they can “take it.”

Many times I could have forced my opinion on the boys and saved Fern perhaps some bitter disappointments—“Let me do it. I’ll manage all this. Let me know when you need anything.” But, instead, I merely stated my attitude and said, “Here are the two alternatives. You want this; I think the other is better. Neither of us can tell which is right. If you choose your own way I’ll help you as long as you do it well, providing you stop as soon as you know it is wrong and go back and pick up the other. If experience teaches you a greater wisdom, you can call it square.”

At Peddie Institute, Stuart was paying more attention to sports than studies. It was easy for him to be an athlete. But he also had a logical mind and a quick ability for co-ordinating hand and brain. When he was ready for college he entered Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University. His imagination was soon captured by archaeology and medicine, but his course was already set.

Meanwhile Grant, who had been inclined to hero-worship his older brother, had also gone to Peddie. His athletics left little opportunity for bringing out his artistic talents, and he agreed to take his last two years at Westminster School in Simsbury, Connecticut, where he was encouraged to develop along his own lines. In his sophomore year at Princeton, he still had no idea of what he wanted to do with his life. Although he had a leaning towards diplomacy, which would include training in law, I explained to him that, since the family had no political influence, it might lead to being a small politician.

And so I made out a list of as many occupations known to man as I could think of, and sent them to him, telling him to mark off with a blue pencil those which he was perfectly sure did not appeal to him, and check with red those for which he felt some predilection. Out immediately went piano-mover, waiter, floorwalker, bank manager, bookkeeper, and some fifty others.

Six months later, I returned him the red-checked list for further perusal. Now his preferences were much more definite. Research, journalism, editorial work, diplomacy were again red, but almost everything else marked headed him for a scientific career.

The decision made, Grant began his pre-medical course.

After Stuart graduated from Yale he moved downtown to Wall Street and continued in a broker’s office all during the depression. But, in this money making atmosphere, his attitude was changing. He had concluded that serving humanity was a higher fulfillment than profiting at humanity’s expense, and medicine seemed the career which he also liked best. Having found out, he had the courage to start back at the beginning to accomplish it. We made a compact for him to go as far as he could and test whether his interest kept up. First he had to acquire sufficient chemistry and biology, going to Columbia University in the daytime for the former, to New York University in the evening for the latter, preparing his lessons until three in the morning.

The next year he passed his entrance examinations.

Following the legislative near-victory in the winter of 1934, I resolved to go to Russia to see for myself what was happening in the greatest social experiment of our age. With keen anticipation I looked forward to discovering whether the Marxian philosophy, dramatized and realized and based on an economic ideology, did not have to accept some of the philosophy of Malthus.

Grant, then about to enter his final year at Cornell Medical School, was eager to investigate the progress of medicine in the Soviet Union, and made up his mind to come along. I was taking also my secretary, Florence Rose, efficient, competent in any capacity, whether field organizing or in the office. Though but recently enlisted in the movement, she had come more with the attitude of the early days, not for what she could get out of it, but for what she could give to its furtherance. Her talents and enthusiasm, when added to her cheerfulness, made her a rare combination; always gleeful and bubbling with fun, she carried out nearly everything in that spirit.

Mrs. Ethel Clyde, an officer of the Federal legislative organization, was to be the fourth of our little group within a large group. When zeal for the “new civilization” in Russia had been at its height she had relinquished her expensive Park Avenue apartment for a smaller one on a side street, and contributed the difference in rent to sundry leftist causes and birth control.

At the last moment it seemed we might not be able to go. For some years Stuart had had a bad sinus condition, and hardly had he matriculated at Cornell in the fall of 1933 when he had been struck by a squash racket, fracturing the bone over his eye. That winter he had been operated on nine times. A week before I was due to sail this doctor advised that he have an exploratory operation. I rushed up from Washington, where the legislative work for that session was just being wound up, and would have abandoned the Russian expedition had not the operation apparently been entirely successful. Stuart insisted that I go. Since he was in no danger I continued with my plans.

It was not feasible to travel in Russia except in a party under official guidance. Three people I knew who had gone by themselves described how train after train had passed them, boat after boat had steamed down the Volga with no accommodations available. Therefore, we chose the non-partisan Second Russian Seminar.

Shortly prior to leaving I spent an evening with Maurice Hindus, Will Durant, John Kingsbury, and Drs. Hannah and Abraham Stone, all of whom had been to Russia the previous year. Maurice Hindus had returned impersonal and still unprejudiced, Will Durant utterly antagonistic, John Kingsbury full of fervor, and both Stones warmly disposed. They had all been in Moscow, practically at the same time, for approximately the same number of days, and all had received utterly dissimilar impressions. Even pictures that Will Durant had taken were not the same as those of John Kingsbury or Dr. Stone, snapped from almost identical places, thus showing me how wide might be the variety of responses, depending on the individual bias.

I expected to keep my eyes open, to think independently, to ask questions, and compare. I was going to use as much sanity and fairness as I possessed, and not be swept emotionally into any current of opinion.

Billy Barber was the manager of the Seminar, and I did not envy him his job. There were many complaints and stupid remarks and much faultfinding. Most of the party were going merely to be able to say those things were true which they had previously said were true. I asked one woman who went on every sight-seeing expedition but never got out of the bus, “Why did you come?”

“Oh, just to wipe Russia off my list.”

Edward Alsworth Ross was among the leaders. He was the only person who had been there under the former regime some twenty years earlier, and had an authoritative basis of contrast between the old and the new; we all rather sat at his feet. He was a typical professor, wore enormously high, stiff collars, played checkers with anybody who would indulge him, and was upset when he failed to win. His personality was impressive, literally so because wherever you looked you spied him. One of the funniest sights was to see this Nordic giant, six feet four, walking with short dark Florence Rose, five feet two, each jollying the other.

We scooted through England across to Copenhagen, about which I recall very little. I was always trying to learn what advance the women’s movement had made, but somebody was always trying to tell me how marvelous the city was. Remembering Ellen Key, I reached Scandinavia with great hopes for Feminism. But the women who were considered the most intelligent were complacently resting on their laurels. The older ones still reigned supreme and believed that, because they had won their battles of twenty-five years ago, there was nothing left to fight for. The younger group found it hard to rise above the inertia of this overwhelming prestige. Since population was not a problem in Scandinavia, they were interested chiefly in eugenics, and had almost forgotten the aspect of individual suffering.

At Oslo a number of us went on pilgrimage to the grave of Ibsen. As I stood there in silent tribute I had the feeling he had understood women and the ties they had been loosening. To my mind Nora never went back to the “doll’s house”; her evolution was too complete. Or, if she did return, she entered by another door.

Mr. Barber had arranged to feed his hundred and six charges at the last Finnish railroad station. There was a particular exhilaration about the prospect of that meal, because it was to be our final one before crossing into “famine-stricken” Russia. We arrived at ten in the morning, all of us hungry. As we filed into the station our eyes met the most gorgeous panorama—long tables beautifully laid out with delicious meats, fish, breads, compotes.

While we paused, debating which of these delicacies to taste first, there came a stampede of fifty other Americans, a tourist group led by Sherwood Eddy. Never had I seen such an exhibition. The men, unshaven, hatless, coatless, pushed and shoved around, in front of, and almost on top of the tables. The best we could do was find comfortable seats from which we could have a good view of the riot. The meal prepared by the railroad with such courtesy for our party was demolished by another.

Barber and Eddy eventually discovered it was all a mistake. The train carrying the Eddy-ites had failed to stop at the town where their repast had been awaiting them, and naturally they supposed this breakfast was theirs.

At Leningrad we were met by buses and driven through streets that swarmed with imperturbable, peasant-like people. The upper parts of their Mongolian-shaped heads all looked exactly the same. I noticed how immaculate they were. Faces, necks, hands, were white as white and displayed a cleanliness simply marvelous when you took into consideration the difficulty of securing soap and water. Very few were old; many were children apparently between the ages of two to twelve. But in the expressions of all I glimpsed a sadness.

The former capital was depressing and down at heels, shabby and in need of painting. Yet it was beyond comparison in its spacious dignity; the architectural design of the houses could not be hidden. My high-ceilinged room at the Astoria was luxurious with alcove bed, bath room, and large marble tub, which, although cracked and spotted with rust, nevertheless evidenced the days of splendor when the hotel had been frequented by the aristocracy of the Old Regime.

From my window I could see the cobbled square. It was eight o’clock and the city was awakening. I watched the passing show: heavy wagons were drawn by a single and often most decrepit horse with what seemed a dark brown rainbow, arched and graceful, over his neck; queues formed in front of little stands that served rations of beer or bottled soda water; some women, the varying colors in their shawls making bright splotches, swept the car tracks with birch switches or pushed empty carts on their way to market, others carried hods of cement up the ladders to the masons on the new buildings being erected everywhere. Usually the men were doing the skilled work, and women, hardy and robust, with strong legs, bare feet, sunburned faces, were kept at the laborious, monotonous, physical labor until such time as they could qualify as expert artisans.

The Communists’ apartments were much better, lighter, airier, cleaner, more modern than those for non-party members. When we asked why, in an equalitarian state, one section should be thus privileged, we were answered, “It was they who made all this possible. Why should they not have the best? What you bourgeois give to your capitalists, we give to our Communists.”

We asked Tanya, our guide, if she were a Communist, and she replied, “Oh, no. That’s too hard.” Ordinary citizens might be excused for a mistake or even a crime, but party members could have no human frailties. They were exiled or perhaps shot for cheating, stealing, deceiving, exploiting, taking money under false pretenses, or many things which average people could do and be punished with fines alone.

Although the cost of the trip itself was relatively low, whatever we bought in Russia was excessively high owing to the peculiar situation of the ruble. In the first place, there was no ruble; it existed only in theory. Second, every foreigner was supposed to deal exclusively with the Torgsin stores through which the Government had cleverly contrived to come by a hoard of foreign currency by charging seventy-eight cents in our money for each ruble instead of its actual value of five cents. For example, the price of a stamp on a letter to the United States, which was two and a half rubles, amounted to two dollars.

Mrs. Clyde, who leaned sympathetically towards Communism, said to one of our young men, “Let me get you a little present.”

“Not here,” he said. “It’ll be too expensive.”

“Oh, yes,” she insisted. “What would you like?”

“Well—a bar of almond chocolate, then.”

She had to pay ten American dollars for that ten-cent bar of chocolate. Her Communism melted slightly.

Ultimately, we solved the ruble problem. One morning a boy who had been loitering around the Astoria asked Grant, “Would you like me to take you through the city?”

Grant prudently inquired, “How much?” It appeared that the boy merely desired an opportunity to perfect his English; he had plenty of rubles, which he was glad to dispose of at the rate of fifty for a dollar. Russians could obtain none but the cheapest commodities on their tickets; if they wanted luxuries such as good shirts, leather or rubber boots, and other articles sold only at Torgsin, they were obliged to surrender some treasured gold piece or use foreign money.

With an ample supply of rubles I sent long, elaborate cables to Stuart to cheer him up. He must have thought an excessive maternal solicitude was getting the better of my economic judgment. But, as a matter of fact, one of twenty words was costing me less than twenty-five cents.

Dr. Nadina Kavanoky, who had been interested in birth control in the United States, had given me a letter to her father, Dr. Reinstein, once a dentist in Rochester, New York, now in Stalin’s close confidence. He came to see me about eleven-thirty one night, the Russian calling hour, and we talked until three in the morning. When he wanted to know my “impressions of Russia,” I said promptly, “It seems to me your policy of overcharging us is a mistake; for the sake of a few dollars you are creating ill will, just as the French have done. In our own Seminar we have twenty librarians and perhaps double that number of schoolteachers and students, many of whom have gone without other vacations to come here. They have a unique opportunity to influence people; everybody will ask them when they get back, ‘Did you like Russia?’ You are trying to build up a favorable public opinion abroad, and these people are the best mediums for that purpose. If they are pleased they will fight for you and break down prejudice.”

But he was not convinced, and, evoking the specter of the Tsarist debt to America, he replied, “We’ll bleed you, we’ll milk you, we’ll get every dollar out of you we can. America demands her pound of flesh and this is how we’ll pay you.”

The occasions for receiving “pleasant impressions” were offered by vigorous tours to points of interest. We were given a choice of hard buses or harder ones, all, in my experience, springless and clattering noisily over the cobble-paved streets. After a few bumps we usually hit the roof and came down with headaches. Our poor little guides had to screech with full lung power to be heard over the incessant rattling.

One morning when driving back from sight-seeing, the motor gasped and collapsed on a slight hill. Passengers volunteered helpful suggestions—“Put it in low. Put it in neutral. Push this. Pull that.”

The driver moved gears forward and backward and then looked around at us in perplexity, “I did, but it won’t work.” We waited and waited and waited and waited. Somebody ran a mile to telephone that we were stranded and needed another bus. Meanwhile, everything we wanted to see was closing, and we had already learned that whatever you missed in Russia was always the most worth while. In fact, it seemed they had visiting hours timed to end five minutes before you got there. Several other buses came along and stopped. Their drivers got out, poked their heads under the hood, began taking things apart, strewing bolts this way and nuts that. Then they, too, became discouraged, and, leaving increased confusion, climbed on their chariots again and went on.

Finally some bright young man discovered we were out of gas.

As we crossed the huge square in front of the hotel, I saw directly ahead of us an enormous pile of bricks with wide spaces on both sides. Closer and closer we came. “When will the driver turn?” I asked myself. But he never did; we went right over the top and the bricks slipped out from under. That was the Russian system. You could not go round an obstacle; you must go over it.

Enlarged portraits of Lenin and Stalin were in all public buildings. Their statues were everywhere, in every square, on every corner. A major industry of Russia seemed to be to find new poses for Stalin—standing up, lying down, writing, reading. Often just his head, definitely recognizable in spite of the predominance of red, was designed in flower beds. One of the most delicate attentions was to give him a different colored necktie on different days; the plants were kept in pots to make this charming gesture possible.

After the Revolution when peace had come, connoisseurs from various countries had been invited to examine the recovered statues, rugs, tapestries, and objets d’art stolen from the palaces and churches. One by one the priceless paintings were displayed, specialists rendered their opinions, commercial dealers furnished appraisals, stenographers took down every word. The same was done with the lapis lazuli tables, the snuff boxes, the court jewels.

The interesting part of the new arrangement was that the interpretation was entirely Marxian. Pictures, instead of being hung according to the orthodox history of art, were fitted into the Industrial Revolution. A certain Madonna was not admired for its qualities of color or form, or as a thing of beauty in itself; the guide explained to you that it was created at such and such a time when the Church was trying to get a hold over the people, when artists were starving and had to look for their means of livelihood to the patronage of the Church.

Later, in the Kremlin at Moscow we saw fantastic and incredible riches, jeweled saddles, a whole set of harness studded with turquoise, a huge casket cloth embroidered with thousands of pearls. In order to place the period of the latter I asked Tanya where it had come from. She replied in her precise English, “You see, it is for to cover the dead. You see, in Russia there was such a custom. When they died they put them in the ground. It was such a custom, you see, to cover them with cloths.”

She spoke of the Tsarist Regime as though it had been centuries ago.

One of the pictures was a Christ removed from the cross and lying on the ground. Tanya said, “People used to come here, and they even kissed it!” This she uttered in the tone of scorn of a very youthful generation shocked and horrified at the ancient traditions.

“Our hope is in the young people,” she said frequently.

“But how old are you?”

“Oh, I’m thirty-two,” as though she were doddering.

Grant and I were once walking by a group of children when a small boy pointed at us and remarked, “Ah, there go some of the dying race.” To them all Amerikanski were capitalists.

The Marxian ideology had been applied to every phase of life. H.G., accompanied by Gyp, his biologist son, had flown over from London. Since he wanted an opportunity to go around alone, he rather resented being so closely guarded and courteously guided. After talking with Stalin he had come to the conclusion that the Dictator had no understanding of economics. He was somewhat annoyed at the constant interpretation of everything in terms of politics, and of having Marx stuffed down his throat at every turn.

At the schools you might ask what kind of mathematics they taught.

“Marx.”

“And what system of engineering?”

“Marx.”

No matter what the question, the answer was Marx.

The Anti-Religious Museum, once a cathedral, was directly across from the Astoria. Each half-hour little girls, who seemed hardly more than ten or twelve, their sleeves hanging down over their finger tips, with great dignity conducted excursions of peasants through. Their lecture started with the fundamental principle that the earth was round. A bas-relief of the world was underneath the huge pendulum which hung from the dome. If you stood there long enough you saw it swing from one point to a further one. They were trying to show that it was within man’s power to make his own heaven.

Here were kept the relics of the churches, the icons laden with silver and gold wrung from the poor peasants in the past. Actual concrete things were reduced to their simplest terms on large poster-type murals which depicted stories, a necessary practice since the muzhiks were so generally illiterate. In one a kulak was coming to the priest with a sick child in his arms, asking for prayers to cure its illness. The priest, fat and clad in rich robes, shook his head, saying, “You must bring money for the saint. The saint will not cure your child unless her arms are covered with silver.” But the kulak had only his farm. “Mortgage it and get the money,” the priest ordered. Soon the kulak returned with silver, and the mural showed how now the saint’s arm was almost hidden. But still the child remained sick. “The saint’s halo is bare,” said the priest. At last the whole figure was silvered, but the baby died just the same.

Opposite this mural was pictured the Soviet way. The father carried the baby to the hospital, where nurses with gauze across their mouths took it preciously, bathed it carefully, laid it in bed. The entire sterilizing process was illustrated—the doctor in white gown and cap, scrubbing and washing each hand five minutes as marked by a clock. Finally you saw the child, healthy and well, jumping into its mother’s arms.

The people stood there looking, their imaginations fired. They said, “This is what is happening to us.”

Most particularly I wanted to investigate what had been done for women and children in Russia, to learn whether they had been given the rights and liberties due them in any humanitarian civilization. Grant, Rose, as she was known to me, and I went one day to the Institute for the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood, a vast establishment stretching over several miles, with model clinics, nurseries, milk centers, and educational laboratories. I was overwhelmed in contemplating the undertaking. There was no doubt that the Government was exerting itself strenuously to teach the rudiments of hygiene to an enormous population that had previously known nothing of it. Russia was also aiming to free women from the two bonds 442that enslaved them most—the nursery and the kitchen. All over the country were crèches connected with the places they worked.

Children were the priceless possessions of Russia. Their time was planned for them from birth to the age of sixteen, when they were paid to go to college, if they so desired. No longer were they a drain or burden to their families. Not only were teachers or parents forbidden to inflict corporal punishment, but children might even report their parents for being vindictive, ill-humored, disorderly, and in many cases they did so.

In one divorce dispute as to custody of the offspring, the father argued that the mother was bad. The Judge asked, “Of what does her badness consist?”

“She is nervous and loses her temper.”

The Judge agreed she was not fit for motherhood.

Furthermore, Russia was investing in future generations by building a healthy race. If there were any scarcity of milk the children were supplied first, the hospitals second, members of the Communist party third, industrial groups fourth, professional classes fifth, and old people over fifty had to scrape along on what they could get, unless they were parents of Communists or closely associated with them.

I was eager also to find out what had been done about the study carried on by Professor Tushnov, of the Institute for Experimental Medicine, on so-called spermatoxin, a substance which, it had been rumored, produced temporary sterility in women. I made an appointment with him, but a shock awaited me. He had tried out his spermatoxin on thirty women, twenty-two of whom had been made immune for from four to five months, but now all laboratory workers had been taken from pure research and set at utilitarian tasks such as the practical effects of various vocations on women’s health. Nothing concerning immunization to conception could be published in Soviet Russia, no information could be given out under penalty of arrest, and, moreover, nothing could appear in a foreign paper which had not already been printed in Russia.

Intourist, the Government tourist bureau, and Voks, the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, had asked me when I had first arrived whom I wished to see and where I wished to go, and had offered to call up people on my list and arrange for visits, a service which had saved me much trouble and expense. In spite of this co-operative attitude, I was suspicious that much was being hidden from us. Before I had left America I had heard I could see only what Russia presented for window-dressing, and with this in mind I was on the alert.

Both Grant and I wondered how the hospitals built under the Tsars compared with recent ones. When I asked to be taken to a certain one, I was assured it was too far away, and anyhow it was being renovated; there was nobody there. I said to myself, “Aha! here is one of the forbidden sights. Whoever heard of a hospital equipped to handle thousands of patients being utterly empty? They are not going to let us see this because it might speak in favor of the old in contrast to the new.”

Politely but firmly I insisted. Again I was told there were so many other interesting things it would be a pity to waste my time going to see it. I found it difficult to say anything further without giving offense. Then Grant encountered a young American nurse from the Presbyterian Hospital in New York who spoke Russian; she also wanted to visit hospitals. We engaged a car of our own and drove a good fifteen miles out of the city over horrible roads, winding and dusty and badly paved, and even pushing on as rapidly as we could we did not get there until late in the afternoon. To our dismay we discovered not a patient, doctor, or nurse in the place, only plasterers, painters, carpenters, and cleaners, pulling down and refurbishing. We had lost half a day and were a little ashamed of our lack of faith.

The night came to take the train for Moscow. Nobody called “All aboard!” in Russia. Trains went right off underneath you when you had one foot on the platform and one on the step. They just moved and moved fast. But we clambered on and soon the leather seats were made into our beds; they were so slippery that we kept falling out.

Once at Moscow, we who were coming second-class, according to Marxian procedure, received the worst rooms at the hotel; those who traveled third had the best. I could not applaud the one selected for me. It was directly over the laundry, and the smells of cooking and suds floated through the window. I refused to stay and was accommodated on the top floor where the servants had once lived.

Moscow was as different from Leningrad as New York City from a sleepy Pennsylvania town. The people walked more quickly and seemed to be going somewhere, not simply wandering listlessly. Bedlam existed at the hotels, but by now we were beginning to learn that the Russians were so concerned with their own efficiency that they had no time to do anything. To be in a hurry merely complicated matters. I could wait, but for energetic Rose it was torture. To all specific requests they replied, “It cannot be. It cannot be.” She had her own methods of coping with this, saying she did not wish to hear the word, “impossible”; she had no intention of asking the impossible. Then when they procrastinated with, “a little later,” she countered, “In America we say, ‘now!’”

Her triumph over dilatoriness came on Health Day. Since health was almost a god in Russia, all activities ceased on that occasion and the populace of Moscow came together on Red Square. The spectacle was to start at two in the afternoon, but before it was light you could hear the songs of men, women, and children moving towards their appointed stations.

Out of our party only thirty were privileged to receive tickets, and their names were posted. Mrs. Clyde and I were on the list, but not Grant or Rose. The previous day the numbers were cut to twenty; that morning there were but sixteen, and feeling ran high. “Why haven’t I a ticket?”

Fortunately for me I had been invited to lunch by Ambassador William C. Bullitt, who entertained lavishly and was helpful to traveling Americans. When I had met him back in New England, I had never thought of him as an ambassador, nor as a man skilled in dealing with the great problems that required strategy, diplomacy, political sagacity, and a prime knowledge of economics and history. I considered him rather as amusing, an excellent dinner host, and one to whom you could go when in difficulty, sure that he would get you out. Perhaps this was what Russia wanted at that time more than anything else. No doubt he was then somewhat disappointed at the turn relations between Russia and the United States had taken. Russians on the whole admired him; they had not forgotten that, although he was not counted a proletarian or in the category of Jack Reed, he had lifted the cudgels for them in the early days when friends were needed.

The Ambassador’s little daughter Ann, aged ten, officiated at the head of the table, apparently enjoying herself. The house in which they were living while the new Embassy was being built had an architecture quite befitting what I imagined the style of Russia should be—a bit of the Kremlin, a bit of a mosque, and a bit of an Indian palace.

On the way to the Square after luncheon a wave of people surged between the rest of the diplomatic party and myself, but I kept saying “diplomatique,” and was bowed through to the grandstand.

Meanwhile Rose had been devoting her whole attention to tickets—and there were no tickets. The lucky holders lined up and filed off under a leader. Rose, the ever resourceful, donned a red bandanna and said to the “forgotten men” in the party, “We’ll make our own battalion.” She handed out slips of paper about the size of the tickets and then started, Grant and the Harvard professors following her through the blare of music and the tramping troops and the pageantry of blue trunks and white shirts, orange trunks and cerise shirts.

Whenever anyone stopped Rose she pointed ahead and repeated my open sesame, “diplomatique,” and they let her by until she reached the last barrier. There the guard was suspicious of her password and challenged her. Then she spied another group coming up, dashed over to the leader, and exclaimed, “Quick, please explain that our interpreter has gone on with our tickets!”

The woman looked unbelieving, but still others arrived at that moment, and the Russian system collapsed under pressure. In they all piled, and Rose turned to her unknown benefactress, “You don’t know how grateful I am to you for getting us in.”

The reply was, “You don’t know how grateful I am to you for getting us in! I’m a tourist too, and we have no tickets either.”

Nobody seeing Moscow that day could have thought it a somber place. It was alive with song, happy faces, bright attire. The parade of a hundred thousand or more was one of the most marvelous spectacles for color, form, cadence, geometrical precision that I had ever seen human beings accomplish. Men and women were representing 446all sorts of games and sports—swimming, shooting, tennis, flying. There was nothing tawdry. Each company held aloft beautifully designed placards as it passed Stalin, who stood on top of Lenin’s tomb. The Dictator looked much like his pictures, with his heavy black mustache resembling the wings of a bird of prey.

All day long and everywhere you heard the Internationale, over and over and over again. Each band struck up as it approached the Tomb and kept playing as it swung on. Always the stirring song from those coming up, those far away—overtones, undertones, thrilling, insistent, now loud in your ears, now dimly echoing in the distance, a rhythmic motif symbolizing the onward march of Young Russia.

Margaret Sanger (1938)

Margaret Sanger (1938)

Thank you for your support of Autobiographies and for being a patron of great literature and the arts.

Best wishes!

“Every man has within himself the entire human condition."

~ Michel de Montaigne