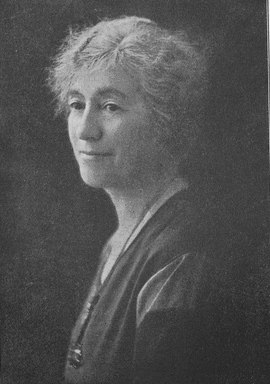

Margaret E. Cousins in 1932

Margaret E. Cousins in 1932

“Divinity sleeps in stones, breathes in plants, dreams in animals, and awakes in human beings.”

INDIAN PROVERB

Several times I had approached the idea of going to India, and always something had prevented me. In 1922 when I was near by, it was the hot season and everybody had gone to the hill stations. In 1928, when I had also made tentative plans, I was not well. I think I had, in addition, been reluctant because Katherine Mayo’s book had left me with such an aching pain I felt powerless to help lift the inertia she described.

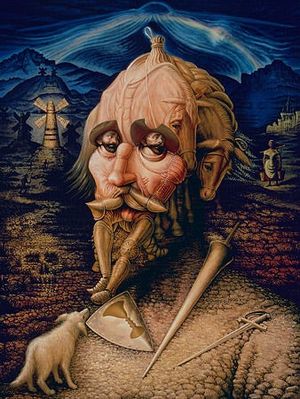

Finally, in 1936, I had word from Margaret Cousins, pioneer in the Indian women’s movement, wife of a poet and university professor, who asked whether I would accept an invitation to attend the coming All-India Women’s Conference. The previous conference had passed a resolution favoring birth control in theory, but now they wanted me to assist them to “put teeth in it,” to draw up one which would outline a practical plan applicable to all castes, to present it, and to argue for it.

Since such a resolution would mean that the movement had now gone beyond the point where we had to break in to be heard, and would start things in the right direction, I arranged to spend three months in India, from November to January, under the auspices of the International Information Center, which had been set up in London after the Geneva Conference so that various peoples and countries interested in the subject might have some means of contact.

Mrs. John Phillips, who had fought many battles in Pittsburgh for birth control, suggested that her daughter, a graduate of Vassar and a newspaper woman, might come along as my secretary. All the way a fine young crowd rallied around the lively Anna Jane, who had as great a capacity for laughter as any human being I ever knew. Nothing was too hard for her, nothing too big or too small for her to do; altogether she was a perfect companion, beginning with our voyage to England, and ending in Honolulu.

Temporarily in London was Gandhi’s appointed successor, Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru, of a family noted for scholarship. He was the youthful leader of the more radical elements in India, much more inclined towards Communism than Gandhi. After having been in jail for four years he had now been released to see his wife who was ill and dying in Germany. I was unable to be present at a reception for him, so Anna Jane telephoned to say I was sorry. “Why should Mrs. Sanger be sorry?” he said, with the simplicity of the truly great. “She can come any time.” I did so the next afternoon.

Nehru was quiet and poised, with a thoughtful manner which impressed you immediately as one of controlled intelligence. His intention was to establish in the mind of Young India that Gandhi’s spiritual doctrines would only be effective if knit with economic and sociological principles.

More recondite than the Indian was the Englishman, Paul Brunton, small and dark, with a solemn, intense, almost mystic expression in his eyes. He was attempting to find what virtue lay in fakirs and holy men, combing India for them, and had embodied the result in his book, The Search in Secret India. He told me, “Not many holy men remain; most of them have gone back into the mountains, inaccessible to Westerners. The one for whom I have the greatest regard is the sage of Arunachala, the Maharshi of Tiruvannamalai. My wife and I have a little hut southwest of Madras, and if you will visit us when you reach that section of India, I will see that you come into his presence.”

Naturally I accepted his offer eagerly and put it on my “must” list.

Shortly before my departure from London, a farewell banquet was given at the Barber-Surgeons’ Hall, a relic of old London known to few, and to which you could be admitted only by invitation. It was on Monkwell Street in the City near the London Wall and Aldersgate. Well aware of the difficulties of threading that maze, even by daylight, I inquired of the carriage attendant at the Savoy whether the taxi-driver were familiar with it.

“Certainly, Madam.”

Off I went with Mrs. Kerr-Lawson, the painter’s wife, somewhat pressed for time. As usual in November, it was raining. After we had serpentined in and out for twenty minutes we began to surmise that the driver was lost, and I called to him, “Don’t you know the way?”

“Well, I thought it was down ’ere, but it don’t seem to be.”

“Why don’t you ask somebody?”

“W’ere’s Barbers’ ’All?” He addressed a mail carrier, who paused to think, and then said, “Well, it’s along there,” pointing back from where we had come.

We turned about but had no better luck. The driver stopped at least ten people, each in uniform or livery of some kind or other, “W’ere’s Barbers’ ’All?” and all we heard was the echo, “Barbers’ ’All?” He drew up beside a bobby; even he did not know.

Finally, we saw smart-looking cars going in a certain direction. We said that must be it, and, sure enough, there on the corner was the sign. For our own peace of mind we were not last. H.G. was close behind us, frothing with fury because he too had been driving around Robin Hood’s barn.

Much of the building was locked up, but what we saw was beautifully preserved. Evidently the Guild of the Barbers had prospered in the days when their members did bleeding and leeching, and attended to other annoyances of humanity, such as pulling teeth.

The dining room, once the operating theater, was now the fairest setting for a dinner that one could have—the service presented by Queen Anne, crystal goblets, a silver rose-carved finger bowl, the vast Royal Grace Cup given by Henry VIII, like a chalice with a six-inch stem, everything used only on rare occasions. The table was like an E with the middle left out, and in the center sat Harry Guy in his high-backed chair above the rest of us. I was on his right and next me was a man whose name had performed almost a miracle for birth control in England—Baron Thomas Horder, then physician to the Prince of Wales.

Sidney Walton, the member without whom this banquet could not have taken place, opened the affair as ancient custom prescribed by declaiming, “Pray, silence for the King!” After the toast to His Majesty, one was drunk to the President of the United States, and then my health was proposed; the loving cup, containing about a quart of red wine, began to make the rounds. During the toast, three people had to be standing—the one holding the cup, the one who just had it on the left, and the one on the right who was to receive it. The waiter came to wipe the lip hygienically when each had swallowed his sip; this was the sole modern touch.

London offered me many courtesies. The Italian invasion of Ethiopia was now in full swing. Rumors were abroad that British ships were avoiding the Suez Canal; therefore, I booked on a Dutch line. When I mentioned this to Sir John Megaw, former director of the Indian Medical Service, he practically stopped breathing and bristled in every hair of his head. “What! a P. and O. boat not go through the Canal for fear of Italy?”

“So I’ve heard.”

“My dear Mrs. Sanger, you can go through the Suez Canal on a British boat if the British Navy has to escort you through!”

Sir John’s report calling upon the British Government to make some plan for population growth, increase, and distribution for India was one of the most intelligent issued by any health officer in this age. Although entirely in sympathy with my project, yet he doubted whether it would be possible for me to do anything. That I was an American, however, he thought might obviate the antagonism which would inevitably follow the mention of birth control by anybody from the British Isles.

Almost as soon as the Viceroy of India sailed, we seemed much nearer the East. Indian deck hands moved about, distinguishable by their slim bodies, brown faces, and turbans, but the English were in command of all departments. It must have been a source of resentment to the Indian passengers to be ignored or treated as inferiors by the English Civil Service going to rule them in their own land.

The ship was second-rate, rocky in a heavy sea, and raucous. The blast of bugles for rising and meals had long since been outmoded on most passenger liners but was retained here. I was awakened at eight or earlier every morning by the most awful thud, thud, thud overhead. After I had had a headache for two days I went up to the sports deck and found the English were getting exercise by throwing quoits around directly above my stateroom.

The Suez Canal was bright with yellow sand and blue sky. We slowly steamed past two Italian transports with bandaged soldiers on the decks, invalided home from Ethiopia. As far as conversation on our own vessel went, no one would have suspected there was a war. Not an Englishman brought up the subject, and, if drawn into a discussion, he eluded it by saying his country could jolly well look after itself.

Once we were in the Red Sea, passengers and officers emerged in white; the decks were roofed with canvas so that the games might go on. Most of these British had traveled so much they had a seafaring routine. They indulged in sports in the morning, dressed appropriately. From two to four in the afternoon a pall of silence descended. All the chairs on the deck were occupied by dozing, browsing loungers. But as soon as the tea things appeared, life began to be interesting. Music burst forth from the orchestra, babies were brought up from the nursery, everybody hurried to and fro from chair to table, picking and choosing cakes or buns, sandwiches or plain bread and jam. After dinner again the full, blazing lights gave ample illumination for the interminable deck tennis and quoits.

Bombay from the distance was a city of tall buildings. Not until very close could you see the sizzling heat on the water; the hot sun and heavy air made it unpleasant to stand on deck. The wharf was filled, the British easily recognizable by their sola topees, the ugliest headgear in the world. All were waving with great excitement, and many carried flower garlands for visitors or those coming home. Amid scrambling and confusion coolies swarmed aboard for luggage. A delegation of about fifty welcomed us, including Edith How-Martyn, who had been sounding out popular and religious sentiment, and Dr. A. P. Pillay, editor of the magazine, Marriage Hygiene, the man most active in eugenics and birth control in India.

I had written to Gandhi and a reply from him greeted me at the boat, “Do by all means come whenever you can, and you shall stay with me, if you would not mind what must appear to you to be our extreme simplicity; we have no masters and no servants here.”

The evening was hot and oppressive indoors but mild and balmy outside, and I sauntered under a lovely, deep sky. The women, small of body, ankles, and wrists, with well-formed features, and softly spoken as the Japanese, whether poor or not, wore bracelets, anklets, rings in the ears, and some a button jewel in the side of the nose. Seldom were any in Western costume; almost always they wore saris, graceful folds draped over their heads. Men and boys were stretched out on the walks, their only belongings the mats on which they lay. It was revolting to see something stir in the dust, and watch rags change into a human being sleeping there.

The next afternoon I had my first meeting in Cowasji Jehangir Hall, the largest in Bombay, and clamorously noisy. It was open to the street, and trams went wobbling by, pedestrians talked loudly, and dozens and dozens of electric fans purred round and round and round. You had to speak at the very top of your throat in order to be heard; Indians were accustomed to the British enunciation and the British pitch and found American English difficult to understand. Looking down on the audience was like gazing at a choppy sea; it was a broken mass of Gandhi white caps, shaped rather like those worn by our soldiers overseas. They were not removed in the house, in shops, or even at table. Everywhere in India you saw them, showing how large was his following.

I had been told that unmarried women did not exist in India and none of the cultured class worked for wages. However, the very day I landed I met three girls who were still single, gave their time to help the outcasts, and had small apartments of their own. Two of them were trying to be independent; another received an allowance from her father who, though disapproving, supplied her livelihood.

It had been predicted also that only Eurasians and the lower classes would listen to me on birth control, but the question turned out to be not, “Shall it be given?” but “What to give?” and it came from all strata. The Mayor of Bombay invited me to address a gathering of city officials. Mrs. Sarojini Naidu, the famous poetess, outstanding for her loyalty to India and next to Gandhi the most beloved person in the country, talked with me about holding a meeting in Hyderabad, where her husband was head of the medical profession. Lady Braybourne during luncheon at Government House told me that she and the Governor were anxious to prevent the fifteen hundred people on their own compound from doubling their numbers within a few years. What would I suggest?

The answer was complicated by many factors. First and foremost was the unspeakable poverty which prevailed. A contraceptive so cheap that it could be available to everyone had been invented in the form of a foam powder which could be made from rice starch; enough for a year should not cost more than ten cents. But as yet we had not tested it sufficiently to guarantee its harmlessness and efficacy.

The poorer women of Bombay, sober-faced and dull-looking, who particularly needed this method, lived in the grubby and deadly chawls—huts of corrugated iron—no windows, no lights, no lamps, just three walls and sometimes old pieces of rag or paper hung up in front in a pitiful attempt at privacy.

I soon learned that when traveling through the country we had to have a servant, or bearer, to secure railroad compartments, make up the beds, see we had food at various stations, and keep the vendors off. Mattresses, blankets, sheets, pillows, towels, and soap had to accompany us on trains. From Cook’s we acquired Joseph, an extraordinary character, dressed always in a black alpaca coat and colorful turban. We paid him about a dollar a day, considered a very good salary. However, since he spoke not only Hindustani, but also Bengali, Tamil, and English, we thought him an excellent find. He waited on us, brought us tea in the morning, went with us on calls.

Joseph’s respect for us was enormously increased when he heard we were going to visit Gandhi. He became our devoted adviser, sleeping outside the door at night. Because of his position it was beneath his dignity to carry anything. Consequently we were obliged to hire a coolie for his luggage as well as several for our own. India was undoubtedly the place for the white man to lose his inferiority complex, should he have one; the serving class was obsequious, and the educated, aloof and superior.

We were met at the station at Wardha by a covered, two-wheeled cart, a tonga, very clean with little steps leading up and drawn by a cream-colored bullock. Since there were no seats, we sat flat on the bottom and were pulled leisurely and slowly along dusty roads to the ashram.

Gandhi was cross-legged on the floor of a room in a large squarish structure, a white cloth like a sheet around him. He rose to greet me as I entered with an armful of books and flowers and magazines and gloves that I had not realized were there until we tried to take each other by both hands. He beamed and I laughed.

Perhaps even more exaggerated than his pictures was Gandhi’s appearance: his ears stuck out more prominently; his shaved head was more shaved; his toothless mouth grinned more broadly, leaving a great void between his lips. But around him and a part of him was a luminous aura. And once you had seen this, the ugliness faded and you glimpsed the something in the essence of his being which people have followed and which has made them call him the Mahatma.

This was Monday, Gandhi’s day of silence, of meditation and prayer. He was so besieged by problems and difficulties on which he had to decide that this one twenty-four hours he reserved for himself without interruption. Therefore, he merely smiled and nodded his head and then Anna Jane and I were escorted along a gravel path to the guest house, perhaps a hundred yards away, a building of four rooms, rough-hewn, white-plastered walls, the upper section open for ventilation. On the uneven stone floor stood two mattress-less cots on which our bedding was spread. A roof pole in the center had a circular shelf which served as table or chairs according to need.

Bowls of porridge and milk were brought, sweetened with either honey or burned sugar—I could not tell which, but it was very pleasant. I asked no questions about its being boiled, or whether it was goats’ or cows’ milk; although I happened not to be hungry, down it went just the same.

From tiffin on we inspected the cotton-growing, the paper-making, the oil press, and the irrigation by means of old-fashioned turn wheels. I was not enthusiastic. It seemed so pitiable an effort, like going backward instead of forward, and trying to keep millions laboring on petty hand processes merely in order to give them work to do by which they might exist.

In the evening Gandhi wrote on his slate that next morning I could join him in his walk. This was his regular exercise, occupying about an hour. He took quite good care of himself physically, observing rules of health and diet rigidly and strictly. He had to in order to perform the tremendous quantity of labor always facing him.

After we had ascended to the roof for evening prayers, our cots were moved out on the terrace under the moon and stars and the glorious, limitless sky overhead. Lights shimmered along the path to the main house but, for the rest, all was darkness. I never was more conscious of nature’s stillness or of more constant stirrings from human beings—the echoing chant from the village near by, singing, calling, laughing, dogs barking, the sounds wafted clearly through the cool and crisp air while not a leaf on the trees trembled. At four the bells rang out for morning prayers and at six Joseph came to tell me the hour and I arose and dressed.

Gandhi and I walked with his other two women guests; they deemed sacred every moment they spent with him. Men, women, and children waited for him as he passed, several prostrating themselves as to a holy person. Stepping over the debris we traversed narrow byways through the open fields where families huddled in their tiny huts together with dogs and goats. People were bathing and washing and cleaning their teeth. Little spirals of smoke were drifting from the fires for the morning meal.

At eleven we all went to our breakfast across the court, leaving our shoes outside. Everybody was ready, and great shining trays of silver-looking metal were placed before us on the floor. Gandhi was trying to persuade the Indians to utilize native-grown vegetables in different ways and thus increase their vitamin consumption. Mrs. Gandhi supervised the culinary department, and herself served the meal, of which there was a goodly and varied supply—no meat, but plenty of fruits and vegetables in curious combinations, such as tomatoes and oranges in a salad. All picked up their food with their fingers, mixing it and scooping it in very cleverly without dropping a morsel.

So numerous were Gandhi’s adherents, so deep his influence, that I was sure his endorsement of birth control would be of tremendous value if I could convince him how necessary it was for Indian women. After breakfast I set myself to the task.

He spoke fluent English in a low voice with accurate intonations, never lacking for a word, and could apparently discuss any subject near or far. Nevertheless, I felt his registering of impressions was blunted; while you were answering a question of his, he held to an idea or a train of thought of his own, and, as soon as you stopped, continued it as though he had not heard you. Time and again I believed he was going along with me, and then came the stone wall of religion or emotion or experience, and I could not dynamite him over this obstacle. In fact, despite his claim to open-mindedness, he was proud of not altering his opinions.

Gandhi maintained that he knew women and was in sympathetic accord with them. Personally, after listening to him for a while, I did not believe he had the faintest glimmering of the inner workings of a woman’s heart or mind. He accused himself of being a brute by having desired his wife when he was younger, and classed all sex relations as debasing acts, although sometimes necessary for procreation. He agreed that no more than three or four children should be born to a family, but insisted that intercourse, therefore, should be restricted for the entire married life of the couple to three or four occasions.

I suggested that such a regimen was bound to cause psychological disturbances in both husband and wife. Furthermore, when respect and consideration and reverence were a part of the relationship I called it love, not lust, even if it found expression in sex union, with or without children.

Gandhi referred me to nature, the great director, who would solve our problems if we depended on her, but said what we were doing was to inject man’s ideas into nature.

To this I replied, “How can you differentiate? Here is cotton growing on your land and lemons also. That’s nature. Would you object to dipping cotton into lemon juice and using that as a contraceptive?”

He said positively that he would. For every argument I presented he countered with “I would devise other methods,” but proposed none that was not based on continence. He reiterated that women in order to control the size of their families must “resist” their husbands, in extreme cases leave them.

Those who listened to the interview declared that the Mahatma made concessions he had never made before. He himself said to me, “This has not been wasted effort. We have certainly come nearer together.” Nevertheless, I knew it was futile to count on Gandhi to help the movement in India; his state of mind would not change. After reading his autobiography, I thought I saw the cause of his inhibitions. He himself had had the feeling which he termed lust, and he now hated it. It formed an emotional pivot in his brain around which centered everything having to do with sex. But there remained his kindness, his hospitality, his arrangements for your comfort, which he duplicated again and again for visitors who gave nothing, but instead received inspiration from him. And, furthermore, since humanity as a rule does little for itself and the inert mass has to be upheaved to a point where it can gain initiative, anyone who can arouse a nation of all classes and ages out of the incredible lethargy into which it has long been sunk and can stir up a people to hope is a great, even noble, person.

Nevertheless, in contrast to Gandhi’s attitude towards birth control, Rabindranath Tagore’s was a comfort. With Anna Jane and Joseph I set out on the long trip to Calcutta—two-thirds of the breadth of India. Now you really saw the country—the palms and banana trees, the natives getting on trains, living in their tiny huts. These were of bamboo plastered with mud and whitewashed; the floors were soaked with cow dung to harden the dirt, and the roofs were thatched with straw. As we passed through village after village, I observed cows, goats, dogs, bullocks, all with their young, rambling in the streets, freely mixing with the people and scrambling out of the way when a whistle or bell sounded. Peddlers, balancing on their heads trays heaped with oranges, walked up and down the station platforms, calling their wares in a fascinating, sing-song meter.

We arrived at Bolpur beyond Calcutta at seven-thirty of an early December evening. Tagore’s son had been on the train and we went with him to Santineketan, House of Peace, where Tagore lived and taught. The grouping of buildings in the thousand-acre estate resembled that of an ancient monastery, not so cozy or individual as Gandhi’s, but rather cold and bare. Before sunrise again I heard the chanting prayers of the students. Boys and girls together then went at six o’clock to study in the mango grove or under the banyan trees, all in the open air.

His former luxurious home Tagore had turned over to his son, and himself occupied a small clay house designed like a temple in modern style. The room into which I was shown in the afternoon was full of books and papers, like the office of a busy executive. Tagore, in a long, rough, handmade robe of homespun, was seated behind his desk. I had been told I would find him greatly aged, but, although he was slightly thinner than when I had seen him in New York in 1931, he did not seem much older. True his beard and hair were scantier, but his face, almost unlined, had the same repose, and his finely modulated voice expressed the same understanding when he spoke of the importance of birth control to his country, and sincerely hoped I would be able to reach the villagers, which he said must be done were it to bring any benefit to India.

Tagore knew I had been to see Gandhi, but did not mention it. He had tact combined with his grace and intellect; he drew, painted, directed dancing, even sculptured and acted. Appealing to more moneyed classes than Gandhi, he guided his school towards furthering culture and the arts as well as improving agricultural necessities.

The medical building in Calcutta had been selected for my first lecture there, but Mr. O’Connor, who was in charge, refused permission. Since the edifice belonged to the British Government, birth control became at once popular with the Indians, and the meeting was transferred to Albert Hall. I was warned we needed as chairman a good strong man with a domineering personality, because it was a rowdy place and trouble-makers always haunted it. However, the association which had asked me to speak had already chosen a woman, Mrs. Soudamini Mehta, who was managing the clinic in Calcutta. I talked against the noise for forty minutes and then Mrs. Mehta, whose voice scarcely carried over the footlights, opened the forum for questions.

Two bearded patriarchs looking like Messiahs were sitting in the front row. One of them hopped up and, without asking a question, began haranguing in unctuous tones. Mrs. Mehta tried to stop him, but could not. The audience tried to yell him down; a few were with him but most were not. Then a fist fight broke out and the second sexagenarian rose and demanded recognition. Someone caught his hands from behind, and another row began.

Finally I said to Mrs. Mehta, “Perhaps they can hear me. Let’s ask them whether they want to listen to these men.”

At once a mighty roar of “No!” went up. Then both the old men erupted again, shrieking. Mrs. Mehta, anger lending strength to her vocal chords, at last called out indignantly, “You’re naughty, and the meeting is now dismissed!” And so, amid shouts of merriment, we broke up.

I had no more lectures scheduled for a time, and accepted with pleasure the invitation of Mrs. Norman Odling to visit her at Kalimpong, in the shadow of Mt. Everest, three hundred and fifty miles north of Calcutta.

In preparing for this excursion I had to decide whether to take Joseph. He was a silent man. Whenever I had requested him to perform any service, from getting the laundry together to looking after the luggage, he had never answered yes or no but had only shaken his head—not a regular shake, but a nodding from side to side as though he were saying, “Well, well, well!” I had usually sighed, “Never mind.” I had grown rather exasperated with what seemed his deplorable lack of enthusiasm, although Anna Jane appeared to like him; being busy in other directions, especially with beaux, she had left many things for him to attend to. Finally I informed Cook’s that we were departing for the North and would like somebody else. When their representative came around to investigate, he said to Joseph, “Do you wish to go with Mrs. Sanger?” Joseph shook his head.

“There you are!” I exclaimed. “He doesn’t want to go.”

At that Joseph put up pleading hands and spoke in Hindustani.

“Yes, he does,” said the Cook’s man. “When he shakes his head ‘no’ he means ‘yes.’”

Before we started Joseph mentioned to me how wintry it was in the Himalayas; he must have an overcoat. I asked whether he had ever been there.

“Yes.”

“Did you have a coat then?”

“Yes.”

“Did someone buy it for you?”

“Yes, always buy it for bearers.”

“Well, where’s that coat?”

“Worn out.”

I questioned Cook’s about that also and was told, “He’s trying to do you. Probably he already has two or three, and if you give him another he’ll just sell it.”

We hardened our hearts, and Joseph had to get along without his coat.

As we progressed north the nights grew cold, the mornings cold, four in the afternoon was cold. Joseph had changed to a hideous black hat which he said was warmer than his turban, but he had no overcoat and began to cough.

We arrived at Siliguri at six of a brisk morning, just in time to watch the rose-colored dawn break over the snow-covered mountains. After a cup of hot but vile coffee we wrapped ourselves in rugs and off we went on the full hour’s drive to Kalimpong, up and around hairpin curves, mostly following the river, often through bits of jungle whence you knew a tiger might spring out on the road any minute. The scenery was the most superb I had ever seen, grander than the Rockies or Pyrenees or Alps, a blend of green tangle and white peaks touching the clear sky, with wreaths of clouds far below.

As we neared Kalimpong there was a distinct difference in the type of native; Thibetans and Nepalese were frequent. The swarms of women looked like squaws, although, instead of papooses, they carried on their backs huge baskets of charcoal or from six to eight massive blocks of stone, all for six cents a day. No horses, no mules, no wagons, only women as beasts of burden hauling these rocks from the quarry to the site, jingling with rings on their ankles and rings on their toes. What struck me as most peculiar was that many of them wore ugly shawls, assuredly products of Scottish mills; the entire hillside was dotted with plaids.

As soon as I reached Mrs. Odling’s home and heard the accent of her medical missionary father, I knew the answer. “We never think of going home to Scotland without bringing some back,” she said. “They much prefer plaids to their own designs.”

Mrs. Odling was a darling, born there in the hills, and was intensely interested in cultivating the industries of the Thibetans, whom she encouraged to come across the border with their handsome silver boxes and brass bowls studded with turquoise. They were not a pleasant-appearing people. It was almost ludicrous to see this delicate woman slapping some of the worst-looking characters heartily on the shoulder and talking to them in their primitive language; it was evident they adored her and would do anything for her.

Kalimpong itself was lovely and sunny, perched on an outer spur of the eastern Himalayas; in the background soared up the mighty, snowy barrier of Kinchenjunga, which screened it from Thibet, and past it ran the high, chill, rocky road to Lhasa.

To reach Darjeeling, which was on the far side of a mountain range, it was necessary to retrace our steps to Siliguri and then go along a magnificent but treacherous road up another valley. Darjeeling itself disappointed me, a hodgepodge of everybody and everything—tourists, riffraff, exorbitant prices on worthless articles, scarcely a few good ones in gift shops. But I had the opportunity of buying for Grant the skin of a tiger shot in a recent hunt, and this beauty was packed in moth balls and sent directly to the ship. Also a case of Darjeeling tea from one of the choicest gardens was delivered to me in Calcutta, whither I now returned.

There a certain Dr. Ankelsaria, an Indian lecturer who had spoken in America on psychology and psychic phenomena, established himself as my interpreter and guide and dragged me willy-nilly to see such sights as the Jain Temple and Crystal Palace. He overheard me telephoning for an appointment with Sir Jagardis Chandra Bose, famous for his ingenious theory that plants breathed. He promptly said, “I know Sir Jagardis very well; I’ll take you there.”

I intimated that Anna Jane and I were the only ones invited, but he said, “Oh, that’s nothing. We all go there to tea quite often.” But when he did not arrive at the designated hour we set off in a taxi, somewhat relieved.

Sir Jagardis was a person of great dignity—elderly, polished, the scientist pure and simple. He seemed to me like a person trying to keep his life clear, without having externals crowd in upon him too closely.

We had hardly finished our tea when to my surprise Dr. Ankelsaria appeared in the doorway and Sir Jagardis inquired, “Do you wish to have this gentleman?” We explained he had offered to bring us in his car.

Soon we walked out to see the garden, where plants of every description were carefully tended, each treated like an only child—this one put to bed early, that one awakened by the sun, this shrank from noise, that loved running water, this craved a moist atmosphere, that needed a desert in which to thrive; he understood the characteristics of each. He himself was disturbed because his flowers did not like the presence of Dr. Ankelsaria and would be affected by it.

From there we stepped into the laboratory, where Sir Jagardis demonstrated the working of his machine. When he placed either nitrogen or carbon on the plant the instrument, which had been almost quiescent, made tiny marks, much as a person’s heartbeat was shown on a cardiograph.

Dr. Ankelsaria pushed in and got out a pencil and notebook. Sir Jagardis at once froze, ceased talking, and asked, “Are you a newspaper reporter?”

“No, I’m a doctor.”

“What are you taking down? I’ll not have it!” Then, turning to me as though I had been guilty of treachery, “My conversation with you was personal and confidential.”

I was profoundly embarrassed and, as severely as I knew how, requested Dr. Ankelsaria to stop his writing immediately.

The night I was leaving Calcutta for Benares, the worthy doctor insisted I have dinner at his sister’s home, a real Indian feast. Among the guests was an amazing individual who greeted me as though we were old friends, and I wondered where in heaven’s name I had ever known him. Then suddenly I remembered—Carnegie Hall four years earlier, jammed to the doors, some woman relinquishing her seat because she thought the subject of the lecture was more important for me than for her, then the appearance of the thick-set Swami from California, black hair hanging to his shoulders, and my amazement that in good old America in the days of the great depression five thousand people could be induced to chorus after him in unison, “I am love, I am love,” swaying, hypnotized by their own rhythm, until the lofty hall vibrated and thundered. At the end of five minutes I had thanked the lady who had given me her place and tiptoed silently out.

Now here in Calcutta I met again the Swami, clad in his ochre-colored robe, back in India for the first time in many years. He inquired after my health, assured me he had been aware of what I had been doing in America, was so sorry I had not seen his home in Los Angeles. I said I would visit him when next I went to California.

Instead of being taken to the train in Ankelsaria’s unpretentious car, I was transported in the Swami’s elegant Rolls-Royce with the top lowered. As we went swishing through the streets, passers-by jumped on the running boards, dozens of others followed us, all wanting to touch the hem of the Swami’s robe. By the time we had reached the station there were a hundred in our wake. I caught sight of Joseph at the gate, and on the platform, with one eye out for me, was Anna Jane surrounded by her formal English friends in evening dress; the train was to depart in a few minutes. When she saw me approaching with the Swami and his retinue she dashed into the compartment to compose her features. Then we stood at the doorway as we pulled out to watch the Englishmen turning away a little stiffly, and the Swami, one of the incongruous but well-wishing acquaintances whom birth control attracts, waving a vigorous good-by.

Margaret Sanger (1938)

Margaret Sanger (1938)

Thank you for your support of Autobiographies and for being a patron of great literature and the arts.

Best wishes!

“Every man has within himself the entire human condition."

~ Michel de Montaigne