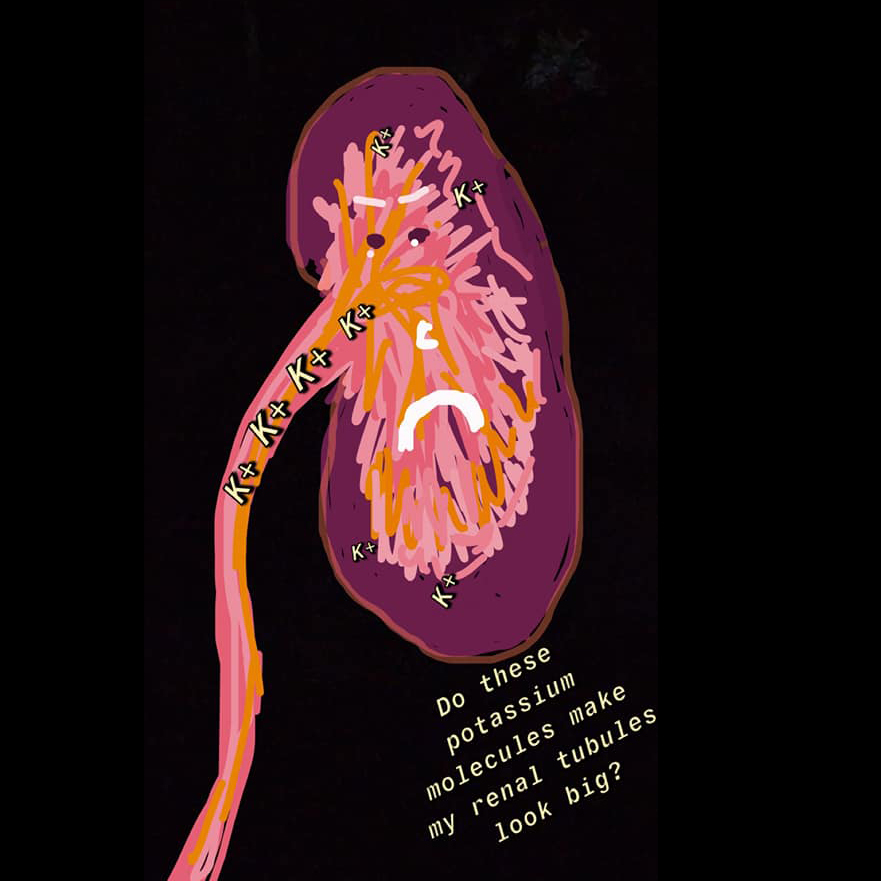

illustration by Stacy Stubblefield, @stacycnm on Instagram. Thank you Stacy!

"God bless us, every one!"

I pen this one week before my upcoming surgery. I'm sporting an athletic-sock rice bag strapped to my lower back, my ubiquitous quart of water jar at my elbow - and frankly - a bitchy attitude.

I'm tired of reading thinkpieces, tweets and blog posts about chronic pain. These writings rarely offer anything new for me. I have moved past "wishing 'normal' people understood" and long ago I got bored with self-pity. But that doesn't mean I can simply wave away my reality.

I live with the genetic disorder of Renal Tubular Acidosis Type II, an impairment in bicarbonate resorption in the proximal tubules of my kidneys. This is a rare condition that more than one scholar has speculated afflicted Charles Dickens' Tiny Tim, the ailing child who is at the spiritual center of A Christmas Carol. The diagnosis can get serious of course - it certainly was for Tim - but for the time being at least I am managing things... okay.

Nevertheless, it sucks. Symptoms of RTA Type II include severe pain in the flank, sides or abdomen; muscle cramps, fatigue, dehydration, decreased alertness, oseteomalacia, increased (or irregular) heart rate, bone pain, and breathing difficulties. My illness means I am almost always experiencing a low-grade ache, and a few times a month excruciatingly painful episodes. Occasionally - as in six days from today - I am treated by surgery which includes the delightful experience of having one (or two) ureteral stents placed.

Here is my list of the eight worst things about my illness.

It scares my loved ones.

No matter how much I reassure them, no matter how "minor" my symptoms may be at times, no matter how responsibly I manage my condition - this illness casts a shadow over our family. My husband and sons love me - very much. They revere me. And they would say I am a hard-working, reliable, contributing member of our family.

But what's it like for my boys watching their parent pace the floor, or lie down and curl up in a sweaty panic? What's it like to sit with me in these waiting rooms - or to listen to me vomit after a procedure? What's it like just those mornings I greet them and I look like absolute hammered ass?

What's it like for my husband to not truly feel free to leave me alone or rely on me one hundred percent? What's it like for him to never be even temporarily, blissfully free of worry? What's it like for him when he tells me he's reserving his healthy kidney donor status for me - "just in case"?

What I wouldn't give for a magic wish that delivers them just a month of not-knowing I was sick - to erase it from their minds.

I feel like I let people down.

One time helming a treatment center meeting for a group of addicts, I could feel a spell coming on. I sat still and nodded as we went around the room, while my blood began to hammer in my ears and my heart raced; sweat formed at my temples and my fingers started shaking. I completed the meeting, we held hands and recited a prayer, and then I calmly turned to my co-chair and asked if he could take me in my car to the hospital. (He had, as it turned out, a warrant for his arrest, no license - and certainly no business driving - but he got me there!)

A dramatic and slightly silly story but these little theatrics play out often in my life. I usually do stick things out; I greet my client for our half-hour meeting or I attend the class. I at least wait as long as I can before excusing myself. (If I ever cancel on you - you'll know I'm really in a bad spot!). If I were to succumb to rest every time I hurt, I'd get very little done - and I want to be part of the human race, I want to be part of my own work, too!

I know myself and I know my limits. So you can imagine how bad I feel, when I can't do what I promised - or I can't do my best. It's gutting.

The symptoms suck.

I live with fatigue, anxiety, constant low grade pain, occasional terrible pain, and muscle weakness. I also live with a GI ulcer from the copious amounts of NSAIDS prescribed to me after my last very unpleasant surgery. Most mornings that's what wakes me up: my ulcer. So I don't get to not-have pain, I just get to live with it.

Being honest about my illness is necessary, but personally uncomfortable.

To many I'm thought of as someone who "puts it all out there" - but I absolutely don't. I am quite calculated and precise about what I "put out" - and when. I'd prefer not discussing my body's medical adventures but I'm affected by them a great deal. It gets to the point where I want to say SOMETHING to my friends and followers and fans - and once I've said something, people are curious, or they start to worry. I feel like I have to then say a little more - to reassure them, to help them understand. And while I know I don't owe them that sharing - only a true heel wouldn't feel that pressure. (Hence this essay!)

It's hard for me to let myself be known, about something I mostly would rather keep to myself.

People give terrible advice.

My condition is complex. I doubt one person reading this essay here could understand even three percent of this paper, published in the medical journal of the European Renal Association. To certain academics and researchers, this article may be readable. To ninety-nine percent of the population, it is incomprehensible.

So when someone tells me to take this supplement, or drink this blend of tea, or go for a ten minute brisk walk, or try this cannabis product, or do this stretch, or tie an onion to my belt - they are demonstrating their ignorance of something they can't possibly understand - and a wee bit of arrogance that they could "fix" me - or even help me.

I know they're doing this because they care, but to put a finer point on it most people simply don't like being reminded of Big Scary Things. They want to help, and (for some of them) they cherish the illusion of Control. ("I'll tell Kelly what to do, they'll do it, they'll feel better - and gee, I just made the world a happier place!")

I have physicians. Those are the people I look to to treat my condition. The general public? My friends? My family? I'd rather they listened to me and acknowledged me. I'd rather they supported me financially! (that helps - a lot!) At bare minimum, I don't want them to prescribe to me.

People give terrible advice, part two.

I am talked down to and talked over if I describe my pain management strategy, which is based on meditation, heat, breath exercises, and yoga. If I bring up any of these strategies I'm told to TAKE DRUGS. DON'T BE AFRAID TO TAKE DRUGS. Et cetera. My plan - overseen and cosigned by my healthcare providers, I might add - forgoes pain medication except for surgery events, and I also eschew any kind of drugs/intoxicants, including alcohol and pot. For the chronically ill, medications and drugs are not the be-all end-all and the afflicted party and their care providers are best equipped to make those decisions.

Medical practitioners often lack empathy

There are obviously fantastic doctors, surgeons, nurses, and medical personnel out there but there is a not-insignificant number who are rude, cruel, abrupt - or inept. As the days count down to my surgery, my dread and memory of past experiences looms large.

For instance: in just a few days I have to go in for a test. The nurse who called me would not answer my questions on which version of the test - a relatively painless one or a rather invasive one - I was scheduled for. I had to ask four clarifying questions before she admitted - with exasperation in her voice - that I was in for the unpleasant version. She was annoyed that I wanted to know.

Lowkey I do believe I have the right to know what's going to happen to my body.

I have plenty more examples. For too many medical personnel, if we don't seem like we might absolutely perish in the next five minutes - I guess we don't deserve empathy, or even the option for informed consent. Empathy goes a long way for someone ill, and in pain. I'm not asking my doctors to "fix" me; I am asking for my dignity to be respected.

I feel trapped in my body

The truth is almost all of us will live through illness, affliction, disability, and impairment - and we all face death. If you're not aware you're trapped in your body then you're just living in a state of blissful disillusionment (hi! welcome to the club!).

Most days I cope well enough that I can work. Some episodes I simply cannot. During those times I feel a panic that is hard to describe (and no it's not Capitalism - it's me wanting to work, because I love my work)! Those are the days that the love, support, humor and shitposting of my friends and family is everything to me. If I can't work: I can at least laugh.

***

There are a few surprising benefits to my illness - true silver linings, the kinds of things we are wont to say "build character". For instance: every day that my pain is at its minimum, I feel so grateful. Every person who delivers a kindness or puts a couple bucks in my coffer - I am conscious of a deep and sublime gratitude almost impossible to express.

And obviously every hour I can work, or take a walk with my partner, or enjoy a coffee roadtrip - I'm blissfully happy!

In a weird way, being ill keeps me humble. I'm always looking for improvement, I'm keeping my mind open to a solution or at least a partial solution. I'm not going to collapse into self-pity. But I'm not going to beat myself up that I'm not "better" yet, either. I'm doing the best I can! Being ill keeps me on a balance beam. In a way, it keeps me cheerful.

Thanks for holding my hand as I walk along this path. Sorry if I shake a little; but I know you understand.