Reward charts, point systems, and other behaviour management programs touted as “positive” are actually out-dated, harmful, and ableist AF.

Written by Jillian Enright, CYW, BA Psych.

Note

This article was originally posted on my Medium blog on September 10, 2021.

Please click here to visit the table of contents for all my Medium articles.

I Am Grateful for Teachers and School Staff

First off, I want to express my gratitude to all teachers and school staff everywhere. You have supported our children and students through some very challenging times, and have rarely, if ever, been given due respect for your work.

Teachers are under appreciated, underpaid, and under-resourced. I have worked in schools in various roles, and I have met some amazing teachers and school staff. There are many who go way above and beyond to provide the best possible education and support to their students.

My criticisms here are not of teachers themselves, but of some classroom management strategies teachers are taught. Our knowledge about children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development has grown exponentially over the past 10–15 years, yet our education system lags well behind.

While some school divisions have made efforts to catch up to what current research clearly outlines as best practices, and offer their staff professional development in line with this framework, many schools still operate in the dark ages.

Even when particular teachers or school staff are seeking to evaluate and improve their pedagogy, some administrators are not very supportive, and professional development opportunities — or funding — may be scarce.

With that said, I am going to spout off about something that has been very clearly established to do more harm than good, yet continues to be present in almost every elementary classroom in North America and beyond.

Those bloody behaviour charts.

Teachers: I appreciate and respect you, but if you have a “behaviour” chart or any kind of reward system in your classroom, please get rid of it now. I’ll explain why.

Behaviour Management Charts are Ableist

“Traditional discipline works best with the children who need it the least, and works least with the children who need it the most.” — Dr. Lori Desautels

Behaviour charts are often touted as positive behavioural intervention, because they are said to encourage children to make “good” choices, and then be rewarded for desired behaviour.

In order for that to work, the child needs to be thinking about the potential outcome of their behaviour at the moment they are performing an action. Depending on the child’s age, they may not even be developmentally capable of doing so in all contexts.

Even if most children of that age group are, or may be, capable of such forethought, there are many children who lag behind in certain areas of their neurological development.

For example, children with ADHD are said to be approximately 30% behind their neurotypical peers in terms of their Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) development (Barkley, 2015).

“Kids with ADHD have immature impulse control and frequently act in ways they regret and, as a result, lack confidence that they’ll handle things well. Things get worse if they’re corrected or told to stop repeatedly, as if they could simply behave through their own willpower.” — (Stixrud & Johnson, 2019).

Children with ADHD aren’t the only ones who may experience this delay, however. Children with frontal lobe seizures, acquired brain injury, trauma (Nelson & Gabard-Durnam, 2020) or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), PTSD (Herringa, 2017), sleep disorders (Hoyniak et al., 2019), among others may also experience similar executive functioning challenges.

The PFC is largely responsible for impulse control, forethought, motivation, judgement, decision-making, planning, and the ability to delay gratification.

Well, that list covers just about anything that would be listed on a behaviour chart: raising your hand before speaking, sitting still, waiting in line, sharing, using an inside voice, and many more.

A great many neurological differences can change how children perceive, process, behave, learn, and develop. Some others include learning disabilities, depression, anxiety, and Autism.

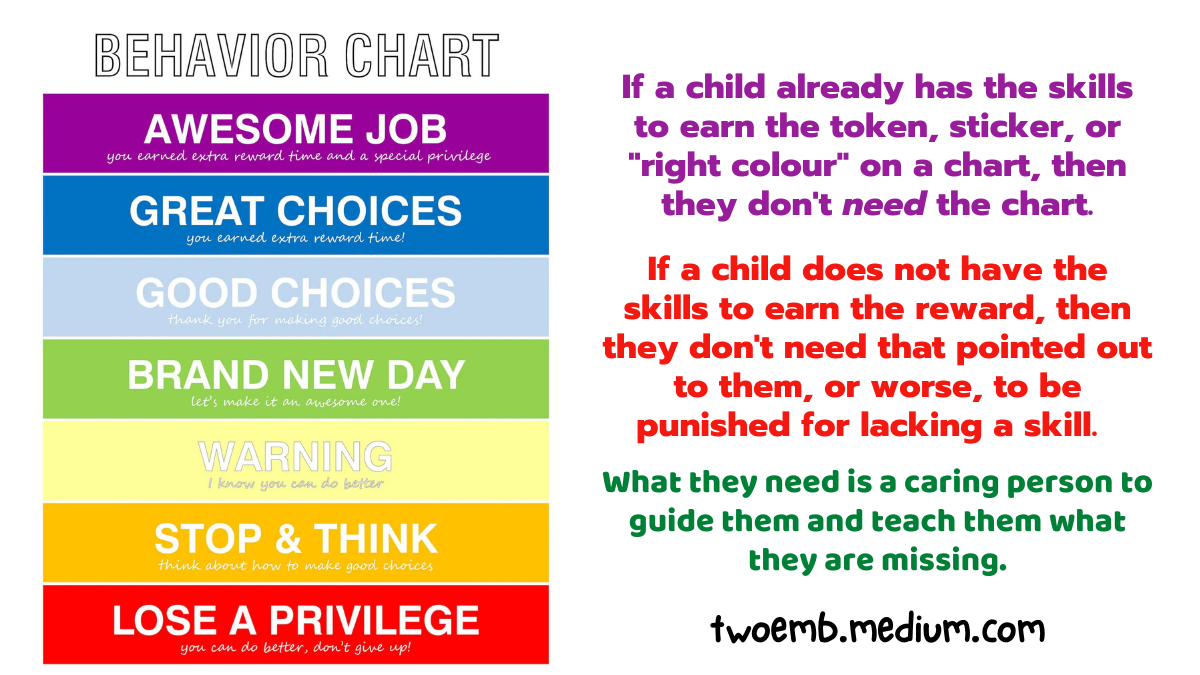

So the children who already have the ability to follow the classroom rules the majority of the time continue to be rewarded for doing something they already know how to do.

Meanwhile, children who lack the neurological maturity, or for other reasons beyond their control are not always able to follow the classroom rules, are then punished for their inability to do so.

“But we’re not issuing punishments, this is a positive behaviour plan,” you say? I know you believe that, but I’ll explain why that position is misguided.

Lack of reward is punishment

The removal of a reward is, in itself, a form of negative punishment. The threat of missing out on a reward is a punishment.

Negative punishment is defined as punishment that results because some stimulus or circumstance (i.e. a reward) is removed as a consequence of a response (i.e. a behaviour, or lack thereof).

For example, if an employee receives a commission or bonus when they surpass a certain benchmark, but fail to meet that bench mark one month and miss out on their bonus as a result, that is a form of negative punishment.

If most of the class receives a sticker for remembering to bring their homework to school, but a few students do not, this is punishing to those students for a number of reasons.

I will cover some of those reasons below, and also wish to point out that many of the reasons I will list may also serve to worsen or increase undesired behaviours, rather than “encouraging” desired behaviours.

They often publicly shame children

Where do most of these behaviour or reward charts usually hang in the classroom? On the wall, or right at the front of the class?

What happens when the students are asked to walk calmly and line-up at the door to go outside for recess, and a couple of them get a little too excited, running or jostling for position in line?

Often the teacher will say something like, “thank you to my friends who walked nicely!” and put a sticker beside their names. Everyone can see which students missed out, and often it’s the same students, the ones who struggle with impulse control and self-regulation, whose names are most obviously lacking in stickers.

Even worse are those coloured charts with clothes pins marking students in various colour-coded zones. They’re often really cute and phrased with positive language, but at the end of the day, they’re incredibly condescending, and sometimes even humiliating.

Here’s one example:

In this system, the teacher has a clothing pin for each student, with name on it. Everyone starts in the green zone as they enter class in the morning. If the teacher notices behaviours that belong in any of these colour-coded zones, the teacher moves that student’s pin into that section.

Again, this is often done in front of the entire class. Sometimes this happens while the teacher interrupts her lesson to walk over to the chart, and moves someone’s pin while all the students watch, humiliating the child whose pin gets moved into one of the “warning” or “bad” zones.

Children whose pins spend a lot of time in the lower half of these charts are often labelled as “problem” kids, even if teachers never say anything like that out loud. Children are smart, they notice patterns, and they observe exactly how the adults treat and respond to the children around them. Whether intended or not, peers begin to zero on on the so-called “bad” kids and now those children are developing reputations, sometimes as early as Kindergarten.

They undermine intrinsic motivation

Children whose behaviours are constantly being manipulated by external factors, namely adults imposing punishments and doling out rewards, end up being reliant on tangible evidence of their “goodness”.

“Incentives like sticker charts, consequences, and other forms of adult monitoring that are “laid on” children actually undermine their self-motivation… Rewards can erode self-generated interest and lead to interest only in the reward itself.”

— (Stixrud & Johnson, 2019).

This can rob children of the ability to be kind for the sake of being kind, or because it simply feels nice to do things for others, and of the ability to see themselves and their choices as positive without needing someone else to affirm this for them.

“External motivators can reinforce the idea that someone other than the child is responsible for their life… relying on someone else’s pronouncement that they are worthy or smart.” — (Stixrud & Johnson, 2019).

They cause anxiety & unhealthy competition

Students in classrooms that operate in this way can become fixated on achieving and receiving the promised rewards, to the point where they are very distressed or upset when they do not succeed.

There are even some behaviour management programs that outright pit students against one another. For example, the class may be divided into groups of students to avoid individual competition, in an attempt to promote “positive peer pressure” and teamwork.

If the group with the most points at the end of the week wins a prize, then how do students treat each other when someone is responsible for their group missing out on points, or not winning the prize? How does that student feel when their classmates are blaming them for losing a point or missing out on a reward?

“The central message of all competition is that everyone else is a potential obstacle to one’s own success.”— Alfie Kohn

Not-so-positive peer pressure, I would say.

Little room for error (aka being human)

As an adult, have you ever gotten away with doing something you weren’t supposed to? I know I have. For example, I’ve been late for an appointment and drove over the speed limit, but was lucky enough to not get a speeding ticket. I got away with speeding, which is a potentially dangerous behaviour.

When children are under near-constant adult supervision, they are often called out on just about every single mistake they make, and this frequently happens in front of their peers.

Even worse, children who struggle to conform to school behaviour expectations are often under the microscope more than their peers. Not only are they already singled out because of their neurological or behavioural differences, they are watched more carefully, and then further alienated because their misdeeds certainly don’t get missed.

Lastly, when adults are constantly directing and controlling children’s behaviour, they don’t have the opportunity to develop self-monitoring and self-management skills… because someone is always doing that for them.

They are manipulative

“Behaviour management is about the adults”—Dr. Lori Desautels (Desautels, 2020).

These behaviour management programs, however positively framed, are primarily about controlling the behaviour of children in an attempt to make the adults’ lives easier.

Unfortunately, this often misses the point, and sometimes makes things worse instead of better.

“Although adult-imposed consequences might be effective at modifying a student’s behaviours, they don’t solve the problems that are causing those behaviours.”

—(Greene, 2021).

I get it, honestly, I do. I have one neurodivergent child. He’s an only child, but sometimes his energy levels and support needs make it feel like I have at least five children.

I’ve worked in schools and in classrooms geared primarily for neurodiverse children. I cannot imagine trying to provide an education to a room of 30 children, as well as trying to keep the chaos to a minimum. Truly.

That said, when we use rewards and consequences just to get the behaviour we want from children, we are indeed manipulating them for our own benefit. However it may seem to also be for our own sanity, it’s not ethical, and does not teach children the tools and skills they need. In fact, it can often backfire, especially with differently wired kids.

“When they feel forced, kids resist even things that are helpful to them in order to gain a sense of control.” — (Stixrud & Johnson, 2019).

Nobody likes to feel manipulated or forced into anything, but I think this is especially true for neurodivergent people. I know I’m heckin’ stubborn and never want to be told what to do. So much so, I wrote a separate article all about power struggles:

Power Trips Lead to Power Struggles

“When a teacher is sitting in judgement of what you do, and if that judgement will determine whether good things or bad things happen to you, this cannot help but warp your relationship with that person.” — Alfie Kohn (Kohn, 2018).

They’re Reactive, not Proactive

Rewards and consequences happen after a behaviour has already occurred. If a student behaves in a way their teacher does not like, having their clothes pin moved, or missing out on a sticker only reacts to the surface behaviour.

“Rewards do not require any attention to the reasons that the trouble developed in the first place.” — Alfie Kohn (Kohn, 2018).

If children struggle to meet their school or classroom expectations, then rewards and consequences are only going to make the child feel poorly about themselves. As I’ve said before, punishments don’t teach skills. Often they only blame and shame.

“By the time a concerning behaviour occurs, you’re in crisis management mode… and behaviour modification strategies don’t solve any problems.” — (Greene, 2021).

What Can We Do Instead?

We can engage in Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS), a child-centred problem-solving model developed by Dr. Ross Greene. We dig deep, with the child leading the way, to uncover the underlying causes of concerning behaviours.

We empathize with and validate children’s feelings and experiences, and work with them to come up with strategies that will work for them. I have written a number of articles on these topics as well:

Help with Challenging Behaviours in Children

Kinder, More Effective Alternatives to Punishment

In Summary

For those who like lists, here’s one of just some of the reasons behaviour management programs should go the way of the Dodo:

They’re ableist

They’re punishing

They publicly shame children

They undermine intrinsic motivation

They cause anxiety and unhealthy competition

They leave little room for error (aka being human)

They’re manipulative

They’re reactive rather than proactive

(c) Jillian Enright, ADHD 2e MB

-

-

References

Barkley, Russell A. (2015). Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis & Treatment. The Guilford Press.

Delahooke, M. (2019). Beyond Behaviors: using brain science and compassion to understand and solve children’s behavioral challenges. PESI Publishing.

Desautels, L. (2020). Connections Over Compliance: Rewiring our perceptions of discipline. Wyatt-MacKenzie Publishing.

Greene, R. W. (2021). Lost & Found: Unlocking collaboration and compassion to help our most vulnerable, misunderstood students, and all the rest. (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Herringa, R.J. (2017). Trauma, PTSD, and the Developing Brain. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(69). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0825-3

Hoyniak, C.P., Bates, J.E., Staples, A.D., Rudasill, K.M., Molfese, D.L. and Molfese, V.J. (2019). Child Sleep and Socioeconomic Context in the Development of Cognitive Abilities in Early Childhood. Child Development, 90: 1718–1737. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13042

Kohn, A. (2018). Punished by Rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt Publishing.

Nelson, C. A., Gabard-Durnam, L. J. (2020). Early Adversity and Critical Periods: Neurodevelopmental Consequences of Violating the Expectable Environment. Trends in Neurosciences, 43(3): 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2020.01.002

Stixrud, W. & Johnson, N. (2019). The Self-Driven Child: The science and sense of giving your kids more control over their lives. Penguin Books.

-

Originally posted at twoemb.medium.com